The Seeker’s Guide to Amanita Muscaria

The Seeker's Guide to Amanita Muscaria

There is, perhaps, no species of mushroom that has inspired as much folklore and purveyed as much mystery as the picture-perfect Amanita muscaria. From age-old Siberian shamans through the Vedic soma, Nordic vikings, and ancient Romans, to Super Mario World, Alice in Wonderland, and the story of Santa Claus, it’s safe to say that the fly agaric is one ubiquitous fungus.

Used for thousands of years by peoples distant culturally and geographically, carried from its Siberian origins across the Bering Strait into the Americas, and across Asia into Europe by the ancients, Amanita muscaria has, since recently, after a long hiatus due to its not-always-pleasant effects, made its way back into the contemporary plant medicine scene.

Praised for its therapeutic benefits, including the alleviation of pain, anxiety, and depression, as well as for its potential to stimulate creativity and reasoning, it’s being used by a growing number of people looking to heal and enhance their lives. Especially as a legal alternative to other ‘magic’ mushrooms, the popularity of A. muscaria as a medicine, when consumed in moderation and with the right intentions, continues to rise.

Table of Contents

Amanita Muscaria Appearance

With its vibrant red cap speckled with white flakes, this picturesque, intoxicating, and potentially nauseating toadstool is easily spotted in the damp forest surroundings where it grows in abundance. However, this iconic image only corresponds to a certain phase in the life cycle of Amanita muscaria, and to two of the total four known varieties of the species.

When just emerging from the ground, its cap is completely covered in pointy white warts. As the caps expand in size, the whitish membrane breaks and the red pellicle starts showing through until eventually the cap becomes mainly red with white warts distributed more or less evenly across its surface.

The cap typically changes from round in young to hemispherical in advanced fruiting stage, and finally to flat in mature specimens. When fully grown, the diameter of the cap is usually between 8–20 cm (3–8 in), while the stem grows to about 5–20 cm (2.0–7.9 in) in length and 1–2.5 cm (0.5–1 in) in girth.

As time goes by, the red color of the cap may fade and become orange, and finally yellow. Rain accelerates this process, and heavy pours can also wash away the white flakes, leaving a smoother cap which is easier to mistake for other species.

Amanita muscaria specimens in various stages of growth

The above description applies to Amanita muscaria var. muscaria (the European and Asian variant) and Amanita muscaria var. flavivolvata (the typical variant found in North America, sporting the same bright red cap but yellowish instead of white flakes). Two other varieties of this species are known so far: guessowii aka formosa, and inzengae; they are distinct from the ‘originals’ in that their caps are yellow-orange rather than red; additionally, the stem of inzengae can be dark. Their chemical properties are similar, although the levels of active compounds may vary.

The History of Amanita Muscaria Use

The use of Amanita muscaria as a religious, divinatory, therapeutic, and social tool extends thousands of years in the past and its records can be traced back to ancient history in most continents.

It’s thought that the use of this mushroom, as well as the species itself, originated in Siberia, [1] possibly as long ago as 4000 BC - linguistic analysis of the Uralic language [2] spoken at the time reveals that the root word pang was used both for the state of intoxication as well as for the fly agaric mushroom, implying that the speakers may have been aware of A. muscaria’s effects.

In western Siberia, it’s known that shamans have used Amanita muscaria to achieve trance states. In eastern Siberia, both shamans and ordinary community members are known to have used it recreationally as well as religiously.

There are records of these shamans serving as something of a toxin filter for the others - they would eat the mushrooms, and others would drink his urine.[3] Some reports also indicate that the villagers would hunt and eat reindeer,[4] which often consume the fly agaric mushrooms, in order to get intoxicated from their meat; other accounts suggest that they would drink reindeer urine [5] to achieve the same result.

After eating Amanita muscaria, excreted urine still contains unmetabolised ibotenic acid and muscimol, the psychotropic compounds found in this mushroom species. As such, it appears to serve the same intoxicating purpose that eating the mushroom does, but with fewer negative effects such as sweating and twitching due to the breaking down of other compounds responsible for these effects.

Interestingly, traditional tales of Central Asia suggest that shamans would wear special outfits when going out to collect the fly agaric mushrooms - red pants and coats with the collar and cuffs fitted with white fur, as well as black boots. After collecting the mushrooms in a special sack, they would return to their village and visit the homes of the villagers, delivering the mushrooms to them. Because the doors would often be buried under several feet of snow, they would sometimes have to enter the yurts through the smoke hole on the roof. The villagers would hang the mushrooms in a sock, and dry them near the fire.

It’s likely that the Santa Claus story was inspired by this practice.[6]

Shaman Claus?

Various archaeological evidence such as cave paintings, wood carvings, and sculptures with Amanita muscaria motifs have also been recovered, and they suggest that the psychoactive effects of this mushroom have been employed in similar shamanic and recreational practices by groups both geographically and culturally distant.

For example, petroglyphs along the Pegtymel River in north eastern Siberia, home to the Chukchi culture, who are known to have traditionally used A. muscaria as an inebriant, depict anthropomorphic figures with mushrooms appended to their heads.[7]

Some myths and sculptures from Mesoamerica also suggest the use of fly agaric in Guatemala and southern Mexico around the time of the creation of the Mayan civilization (1500 – 1000BC); these ancient cultures appear to have associated A. muscaria (which they called cakuljd ikox; cakuljd = lightning, ikox = mushroom) with their Lord of Lightning, Rajaw Cakuljd, and believed that the fungus is born from the place where the lightning strikes.[8]

There are additional records of A. muscaria’s use in North America by the Dogrib Athabasca tribes in the Mackenzie Mountains in Canada, as well as in the ceremonial practices of the Ojibwa and Ahnishinuabeg Indians in the Lake Michigan area of the United States, who referred to this mushroom as miskwedo and whose practices survived until at least the end of the 20th century.

It’s likely that the migrations of people from the Asian continent to the Americas via the Bering Strait were responsible for the propagation of both the mushroom and the knowledge of its ritual and recreational use.

The first Western report on the use of A. muscaria was made by Filip Johan von Strahlenberg, a Swedish soldier who had spent twelve years in imprisonment in Siberia in 1730. He noted how A. muscaria was used as an intoxicant in shamanic contexts:

The Russians who trade with them [Koryak - a tribe on the Kamchatka peninsula], carry thither a Kind of Mushrooms, called in the Russian Tongue, Muchumor, which they exchange for Squirils, Fox, Hermin, Sable, and other Furs: Those who are rich among them, lay up large Provisions of these Mushrooms, for the Winter. When they make feast, they pour water upon some of these Mushrooms and boil them. They then drink the Liquor, which intoxicates them; The poorer sort who cannot afford to lay in a store of these Mushrooms, post themselves on these occasions, round the huts of the rich and watch the opportunity of the guests coming down to make water. And then hold a wooden bowl to receive the urine which they drink off greedily, as having still some virtue of the mushroom in it and by this way they also get drunk.

Filip Johan von Strahlenberg, quoted from Wasson 1968, pg 235

At present, the Ostyak and Vogul tribes, west of Siberia, as well as the Kamchadal, Koryak, and Chukchi tribes in the east, continue to use A. muscaria in their rituals. They dry the mushroom in the sun and consume it either whole, in water or reindeer milk, or mixed with plant juices to enhance the flavor.

Another use for the fly agaric mushroom, and how the species actually got this colloquial name, is as an insecticide. One of its active ingredients, ibotenic acid, both attracts and kills flies; therefore, the mushroom’s cap can be broken into a cup of water (or, traditionally, milk[9]), and the soluble compound will attract flies and cause them to get disoriented and/or paralyzed, often dropping and drowning in the liquid after drinking. This practice has been employed in Germanic- and Slavic-speaking parts of Europe, as well as in a few regions of France and Romania since at least the 13th century.[10]

The Pharmacology of Amanita Muscaria

Numerous alkaloids have been identified in Amanita muscaria specimens, with the most present and important ones being muscarine, muscazone, muscimol, and ibotenic acid.[11]

Muscarine is the alkaloid considered to be responsible for some of the occasionally reported negative side effects of A. muscaria such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, and the general feeling of intoxication. For some time, it was thought that this compound was the main psychoactive alkaloid, but eventually the psychoactive properties of ibotenic acid and muscimol were discovered. Muscarine is present in A. muscaria only in trace amounts, typically making up for around 0.0003% of fresh weight.

Muscazone is another toxic alkaloid found in A. muscaria, which may be responsible for the effects of visual impairment, mental confusion, and memory loss. Its pharmacological activity is also minor compared to the two main psychoactive alkaloids detailed below.

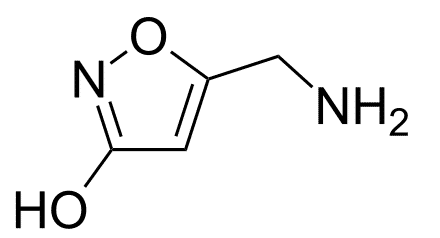

Muscimol is one of the two main active compounds in A. muscaria, responsible for the mushroom’s sedative-hypnotic, depressant, and hallucinogenic psychoactivity. It is a selective agonist of GABAA receptors, and it’s assumed that stimulating these neural sites may be the action behind its reported therapeutic effects. The layer just below the skin of the cap contains the highest amount of muscimol, and is therefore the most psychoactive part of the mushroom.

Muscimol

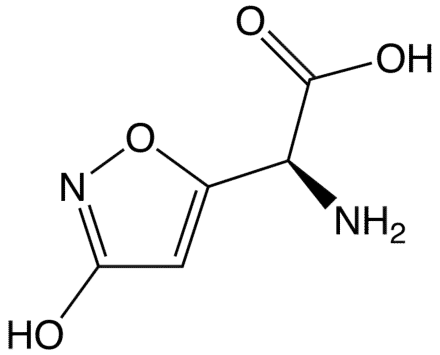

Ibotenic acid

Ibotenic acid is a prodrug to muscimol; the decarboxylation takes place when the mushroom is ingested or dried. As a structurally similar analogue of the neurotransmitter glutamate, ibotenic acid acts as a non-selective glutamate receptor agonist. Ibotenic acid can be toxic at specific doses for each individual, and its toxicity comes from the activation of the NMDA receptors.

Both ibotenic acid and muscimol are psychotropic; the former has more stimulant effects, while the latter has a more depressant action. Their ratio in the mushroom determines the overall quality of the experience to a large extent.

How to Take Amanita Muscaria

As much of the active compound content of A. muscaria is found in the cap of the mushroom, it’s common that the cap is the only part that’s dried and consumed. Additionally, as the stems can contain a large amount of larvae, they are normally discarded.

The mushrooms should be dried until crispy either in a food dehydrator or oven at a low temperature. The process of drying converts ibotenic acid into the more active muscimol, meaning that dry mushrooms will be more potent than fresh ones. It also helps eliminate the alkaloids responsible for inducing nausea.

Warning: Eating A. muscaria raw may result in adverse gastrointestinal effects, reactions to the ibotenic acid, or allergies to uncooked mushroom proteins.

Psychoactive dosage

Although the concentrations of alkaloids can vary widely depending on the altitude and specific ecosystem where the mushroom grows,[12] some general dosage guidelines can be outlined as such:

- Dosage of ibotenic acid: active dose range is 30 – 60mg.

- Dosage of muscimol: active dose range is 6 – 10mg.[13]

Calculating the levels of these alkaloids contained within a certain amount of dry cap flesh, a low dose for a psychotropic experience would be one small or medium size cap (3-5g); an average dose would be between one and three medium size caps (5-10g); and a high dose would be considered as three to five medium size caps (10-15g).

Warning #1: Ibotenic acid and muscimol are lethal in very high doses. A lethal dose in rats has been determined to be 129 mg/kg for ibotenic acid (38 mg/kg for oral intake in mice) and 45 mg/kg for muscimol.[14]

For rabbits, a lethal dose of muscimol is significantly lower at 10 mg/kg.[15]

No data for humans has been published, but some estimates indicate that the lethal dose would be around 15 caps.[16]

Warning #2: Be advised that spring and summer flushes of A. muscaria have been reported to contain up to ten times more ibotenic acid and muscimol than autumn fruitings.[17]

Microdosing Amanita muscaria

The practice of microdosing A. muscaria is a relatively recent emergence, one many have been finding helpful for managing their pain and anxiety levels, boosting well-being, creativity, and clear thinking, and interrupting substance addiction and dependence on psychiatric medication.

As this is still an uncommon practice, advised dosages should only be taken as loose guidelines - everyone’s physiology is different and, therefore, reactions to similar amounts may differ.

According to community reports, dosages between 1 and 3g of dried A. muscaria cap can be considered microdoses. Some people choose to take the dose two times per day.

For best results, the caps may be ground up into a powder to ensure consistency, and then loaded into capsules, taken with a drink, or mixed into a spoonful of honey.

Alternatively, a fly agaric tincture could be purchased online [18] or made very simply by infusing A. muscaria chunks in a high-proof alcoholic drink over a period of two weeks.[19]

Warning: There have been no scientific observations made on the safety of microdosing A. muscaria. Although low doses should not pose medicinal risks to healthy individuals, there is, as of now, no credible data available concerning longer-term ingestion of the active compounds within this mushroom. While available community reports suggest that the practice may be safe to maintain daily over a period of five months,[20] we urge our readers to exercise caution if attempting to microdose A. muscaria.

Cooking with Amanita muscaria

Consuming A. muscaria as a culinary treat is also possible, and many report a delightful nutty taste when this mushroom is cooked or fried. Making it edible and avoiding the psychoactive and adverse side-effects requires that it be ‘detoxified’ first, though.

The alkaloid contents in A. muscaria are water soluble, and heat helps extract them. As such, parboiling the mushrooms in plenty of water for around 15min should yield ready-to-cook fungus flesh. After the water has simmered down, it will contain the active alkaloids; drinking this ‘tea’ should result in psychotropic effects.

Tip: Adding salt and vinegar when boiling the mushrooms reportedly helps extract the alkaloids.

Amanita Muscaria Effects

Depending on the amount taken, mindset, intention, and setting, A. muscaria experiences can vary wildly between individuals.

Generally, on lower doses, one could expect to experience some loss of coordination, a feeling of inebriation, slothiness, euphoria, or drowsiness, as well as some muscular contractions of varying severity, and possible gastrointestinal discomfort. Vivid dreams may be had should the user fall asleep during or after the experience.

On higher doses, more intense psychedelic features can manifest. These include: visual, auditory, and tactile hallucinations, a distortion of perceived sizes of self and objects in the environment, full dissociation and lack of awareness of surroundings, laggy perception resembling watching low-fps videos, the feeling of being stuck in a looping or repetitive behavior or thought pattern, the sensation of flying, and visionary journeys. These can be accompanied by decreased blood pressure, more severe gastrointestinal distress, drooling, vomiting / defecating, sweating, chills, total loss of muscular coordination, and confusion.

The effects can come on quickly, within 15min, but may also take up to two or even three hours to manifest. Waiting for at least two hours is advised over taking an additional dose in anticipation of the effects. The experience typically lasts anywhere from four to eight hours, with no significant after-effects.

Potential Therapeutic Benefits

Risks

Although A. muscaria has the reputation of a “deadly mushroom,” it is decidedly not one. While the following are true statements and present risks to be very wary of:

- Ingesting a large amount of the mushroom without parboiling it can be lethal;

- Even lower doses can create adverse or uncomfortable effects;

- Some of the alkaloids in A. muscaria are considered neurotoxins.

Despite all this, reports of fly agaric poisonings are few and far apart, and very few deaths are known to have happened. Conversely, reports of its therapeutic benefits when taken in moderation are far more abundant.

In reality, the biggest threat does not come from this specific mushroom species, but from mistaking it for one of the similar, yet far more lethal species; make sure to check the next section for more details on which ones to stay away from.

Regarding the possibility of A. muscaria poisoning, it exists, and there is no known antidote. However, the symptoms are rarely critical and the medical prognosis is generally good following supportive treatment.[21]

More serious cases of fly agaric poisoning may present themselves as a state of delirium, characterised by bouts of marked agitation with confusion, hallucinations, and irritability, and followed by periods of central nervous system depression. The rare critical cases may display seizures, loss of consciousness, or a comatose state.

If poisoning is suspected, a gastric lavage may be attempted if time elapsed from ingestion is under one hour; if it’s between one and four hours, activated charcoal is given. Small doses of benzodiazepines can help calm down the agitation, and rehydration or electrolyte replacement may be needed if repeated vomiting manifests. In cases of coma, intubation and artificial ventilation may be necessary.

In the majority of cases, recovery is complete within 12 to 24 hours. Retrograde amnesia and somnolence can result following recovery.[22]

How to Find Amanita Muscaria

Amanita muscaria is native to conifer and deciduous forests of temperate and boreal regions of the Northern Hemisphere. It’s thought that the ancestral origins of this mushroom species are in what used to be the Siberian–Beringian region in the Tertiary Period,[23] but it has since spread throughout the world, presumably aided by the widely transported pine seedlings.

Where

The species can now be found growing in almost any forest in Europe, North America, Siberia, and North-East Asia, as well as in Central America, Colombia, Brazil, South Africa, Southern Australia, New Zealand, and many other countries.

Amanita muscaria forms symbiotic relationships with roots of trees such as pine, oak, spruce, fir, birch, and cedar; as such, it can commonly be spotted growing near to these trees, sometimes in rings around them, known as ‘fairy rings’. It is typically found in abundance where it grows, and is often spotted in groups.

When

Large flushes of Amanita muscaria occur in summer and autumn months across most of North America, but later in autumn and early winter on the Pacific coast. In most of Europe, the season starts around July and extends into autumn, while in more northern countries it can start as late as September.

Remember: Spring and summer fruitings can reportedly contain up to ten times more ibotenic acid and muscimol than mushrooms found during autumn.[17]

An adorable Amanita muscaria on the forest floor

Picking the right mushroom

With the recent surge in interest in Amanita muscaria on account of its rediscovered therapeutic effects, many might consider taking to the woods in search of this mystical mushroom. However, as distinctly recognizable as it may be, it can, at times, be mistaken by more amateur mushroom hunters for similar, yet vastly more dangerous species.

For this reason, we advise extreme caution if foraging for Amanita muscaria, as the results of less than 100% confidence in its identification can be deadly.

Tip: Aside from carefully studying the description of Amanita muscaria in the Appearance section of this page, a characteristic that can be used to identify this species is a yellowish layer of skin just under the top of the cap, which can be revealed upon dissection of a fruiting mushroom.

Here are some similar species and ways in which they differ from Amanita muscaria:

Amanita caesarea: this edible mushroom is a highly valued forest fruit in Southern Europe and Northern Africa, where it is found growing natively. Its smooth orange caps can be mistaken for those of an older A. muscaria, or one whose white flakes have been washed away by heavy rain pour. Luckily, the result of this mistake is a delicious, rather than dangerous bite. Similar species exist in North America - A. arkansana and A. jacksonii, as well as one in Mexico - A. basii and India - A. hemibapha.

Amanita cesarea

Amanita parcivolvata

Amanita parcivolvata: commonly found throughout the southeastern USA, this species is also referred to as the ‘Ringless False Fly Agaric.’ Because of its red color and scattered whitish warts, it’s often mistaken for Amanita muscaria; however, the latter is distinct in that it has more prominent warts, a ring, and a distinctive stem base encircled by concentric shaggy zones. It’s unclear whether this species is edible, or even if it may be dangerous.

Amanita persicina: commonly known as the peach-colored fly agaric, this mushroom can resemble A. muscaria when the latter is in its orange/yellow phase (older) specimens, or the orange / yellow guessowii aka formosa variants of A. muscaria. It grows a bit taller yet smaller in volume than the A. muscaria, and it contains the neurotoxic compounds ibotenic acid and muscimol, although in variable amounts. It requires similar preparation to be safe to consume.

Amanita persicina

Amanita pantherina

Amanita phanterina: also known as the panther cap, false blusher, and the panther amanita, this species is more distinct in that its cap is a light brown. Like A. muscaria, it contains ibotenic acid and muscimol, with the level of the latter compound being greater. Due to this difference, the experience reportedly has more depressant qualities, and the associated poisonings are more of a comatose nature, compared to the confused, agitated states resulting from A. muscaria. It requires similar preparation to be safe to consume.

Amanita bisporigera / ocreata / virosa / virosiformis / verna / exitialis / magnivelaris: these are some of the species of Amanita which are commonly referred to as 'destroying angels' or 'destroying angel chiefs.' Ranked as some of the most dangerous mushrooms we know of, these all-white fungi contain a variety of amatoxins, phallotoxins, and virotoxins, and can easily be deadly to humans. The good news is that the only way they can be mistaken for Amanita muscaria would be if one thinks they are picking a very young fly agaric specimen. For this reason, you should only choose mature A. muscaria specimens with markedly red caps.

Amanita bisporigera

Amanita phalloides

Amanita arocheae / phalloides / subjunquilea: also belonging to the Phalloideae subgenus, these three species are collectively referred to as 'death caps.' Equally as toxic as the 'destroying angels,' these fungi are also somewhat similar to Amanita muscaria; however, their darker brown or yellowish caps make for a safe point of distinction. A. arocheae can be found in Central and South America, A. phalloides grows mostly in Europe, but also all over the world, and A. subjunquilea is endemic to East and Southeast Asia.

Amanita Muscaria Legality

The A. muscaria mushroom is legal to possess in most of the world.

USA

Neither the species or its alkaloids are scheduled on the federal level. Only in Louisiana, except for ornamental purposes, growing, selling or possessing Amanita muscaria is prohibited by Louisiana State Act 159.

Canada

A. muscaria is not scheduled.

Australia

Muscimol is a Schedule 9 substance, making A. muscaria illegal to possess.

Europe

There are no regulations concerning A. muscaria throughout the continent, excluding the Netherlands and Romania, where possession is prohibited by law.

FAQ

Is Amanita muscaria psychedelic?

Yes, it is. The main active alkaloids found in this mushroom, ibotenic acid and muscimol, are both psychotropic and can induce powerful perceptual distortions and visionary states.

Is Amanita muscaria poisonous?

Technically, yes. Some of the alkaloids in this mushroom are classified as neurotoxins; however, when dried and consumed in moderation, the chance for experiencing adverse effects is minimal, and, overall, this mushroom is not considered very dangerous.

How much Amanita muscaria to take?

Depending on the effects you desire, anything from a microdose (between 1 and 3g of dried cap) and a strong macrodose (between 5 and 10 caps) should do the trick. Refer to the Dosage section of this guide for more details.

Can Amanita muscaria be yellow?

Yes. Aside from the cap color fading to orange and yellow as the mushroom grows old, there are also two varieties of A. muscaria which are naturally yellow. Refer to the Appearance section of this guide for more details.

What is the difference between Amanita muscaria and psilocybin mushrooms?

While they can both be considered 'magic' mushrooms, their active compounds and the ways they work their individual 'magic' are completely different. Psilocybin is a serotonin receptor agonist, and ibotenic acid and muscimol activate glutamate and GABAA receptors, respectively - this means that both the psychedelic and healing effects have their own distinct qualities for these two sorts of psychoactive fungi. Additionally, A. muscaria is known to cause nausea more frequently and intensely than psilocybin.

References

[1] Nyberg, H (1992). Religious use of hallucinogenic fungi: A comparison between Siberian and Mesoamerican cultures.- Karstenia 32:71-80.

[2] Wasson, RG (1968). Soma: Divine Mushroom of Immortality. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc

[3] Main, D (2013). 8 Ways Magic Mushrooms Explain Santa Story. Retrieved in July 2021 from: https://www.livescience.com/42077-8-ways-mushrooms-explain-santa.html

[4] Retrieved in July 2021 from: https://www.first-nature.com/fungi/amanita-muscaria.php

[5] Letcher, A (2011). TAKING THE PISS: REINDEER AND FLY AGARIC. Retrieved in July 2021 from: https://andy-letcher.blogspot.com/2011/09/taking-piss-reindeers-and-fly-agaric.html

[6] McWhorter, H (2017). Santa and the ‘Shrooms: The real story behind the “design” of Christmas. Retrieved in July 2021 from: https://inhabitat.com/santa-and-the-shrooms-the-real-story-behind-the-design-of-christmas/

[7] Ott, J (1993). Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, Their Plant Sources and History. Natural Products Co.

[8] Lowy, B (1974). Amanita muscaria and the Thunderbolt Legend in Guatemala and Mexico. Mycologia, 66(1), 188-191.

[9] Lumpert, M, Kreft, S (2016). Catching flies with Amanita muscaria: traditional recipes from Slovenia and their efficacy in the extraction of ibotenic acid. J Ethnopharmacol. 187:1-8.

[10] Magni, A (1867). Ex Ordine Praedicatorum de Vegetabilibus libri VII, historiae naturalis pars XVIII.

[11] Michelot, D, Melendez-Howell, LM (2003). Amanita muscaria: chemistry, biology, toxicology, and ethnomycology. Mycol Res. 107(Pt 2):131-46.

[12] Patocka, J, Kocandrlova, B (2017). PHARMACOLOGICALLY AND TOXICOLOGICALLY RELEVANT COMPONENTS OF Amanita muscaria. Mil. Med. Sci. Lett. (Voj. Zdrav. Listy) 2017, vol. 86(3), p. 122-134.

[13] Flament E, Guitton J, Gaulier JM, Gaillard Y (2020). Human Poisoning from Poisonous Higher Fungi: Focus on Analytical Toxicology and Case Reports in Forensic Toxicology. Pharmaceuticals 13(12):454.

[14] Gonmori, K, Hasegawa, K, Fujita, H et al (2012). Analysis of ibotenic acid and muscimol in Amanita mushrooms by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol 30, p. 168–172.

[15] Stebelska, K (2013). Fungal Hallucinogens Psilocin, Ibotenic Acid, and Muscimol, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Volume 35 - Issue 4 - p. 420-442

[16] Benjamin, DR (1995). Mushrooms Poisons and Panaceas: A Handbook for Naturalists, Mycologists, and Physicians. W.H. Freeman & Company.

[17] Benjamin, DR (1992). Mushroom Poisoning in Infants and Children: The Amanita Pantherina / Muscaria Group. Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology, 30:1, 13-22.

[18] https://thejaggedpath.com/products/fly-agaric-amanita-amanita-muscaria-tincture

[19] https://www.shroomery.org/forums/showflat.php/Number/20643485/fpart/all/vc/1

[20] https://www.reddit.com/r/microdosing/comments/f0qrc2/positive_dissociative_effect_with_amanita_muscaria/

[21] Łukasik-Głebocka, M, Druzdz, A, Naskret, M (2011). Obraz kliniczny i okoliczności ostrych zatruć muchomorem czerwonym (Amanita muscaria) i muchomorem plamistym (Amanita pantherina) [Clinical symptoms and circumastances of acute poisonings with fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) and panther cap (Amanita pantherina)]. Przegl Lek. 68(8):449-52.

[22] Satora, L, Pach, D, Butryn, B, Hydzik, P, Balicka-Slusarczyk, B (2005). Fly agaric (Amanita muscaria) poisoning, case report and review. Toxicon. 45(7):941-3.

[23] Geml, J, Laursen, GA, O'Neill, K, Nusbaum, HC, Taylor, DL (2006). Beringian origins and cryptic speciation events in the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria). Mol Ecol. 15(1):225-39.