The Seeker’s Guide to Ayahuasca

The Seeker's Guide to Ayahuasca

Aya, Yagé, Daime, Hoasca, La Medicina, Uní, Nixi Pãe, Natem, Tea

More and more people are drinking ayahuasca, seeking ayahuasca ceremonies and retreats, and receiving life-changing benefits from working with this ancestral plant medicine in an intentional way.

This guide is intended for those intrigued by ayahuasca and wishing to participate in the culture of ayahuasca safely and responsibly. It should be used for harm reduction and education purposes only, and contains no advice about obtaining prohibited substances.

In this guide you'll learn:

- A basic overview of ayahuasca - what it is, where it comes from, as well as the risks

- How to do ayahuasca - from researching your ideal provider, to preparing for ceremony, and integrating your experience

- An overview of ayahuasca culture

Sounds good? Let's get started!

Table of Contents

Part 1:

Ayahuasca 101

This first chapter covers basic information about ayahuasca and its use, so that you, the seeker, have fundamental information about this ancient plant medicine that is being consumed by a growing number of people around the world, in old, new and exciting ways.

You’ll discover what it is, where it’s from, how it's made, and why it’s important to so many cultures. We’ll cover the effects of drinking ayahuasca, and some of the pharmacology behind it.

Lastly, we’ll go into some of the risks of ayahuasca consumption, including the risks that can arise in the process of participating in ayahuasca ceremonies.

This essential information will help you navigate a thriving medicine culture that is diverse, complex, and ever changing, especially as ayahuasca use expands around the world.

What is Ayahuasca?

Ayahuasca is a psychoactive brew and ancestral plant medicine made from the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and the leaves of the Psychotria viridis shrub. Psychotria viridis (also known as chacruna) naturally contains N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), which is a powerful psychedelic substance.

However, when taken orally, DMT by itself gets rapidly broken down by enzymes called monoamine oxidases (MAOs) in your liver and stomach. [1] This is where the ayahuasca vine plays an important role in preventing the rapid breakdown of the DMT. Banisteriopsis caapi contains β-carbolines, which are MAOI inhibitors. The combination of these two plants creates a hallucinogenic tea, that, when consumed, results in a psychedelic journey of several hours.

The name "ayahuasca" comes from the Quechuan language and means “Vine of the Spirits"; it is used interchangeably to refer to the vine itself, as well as the brew.

However, ayahuasca holds an important place in many South American cultures and may be referred to by different names depending on who is using it, including yagé, daime, hoasca and uní.

While ayahuasca has been used for medicinal and spiritual purposes in the Upper Amazon for at least a millennia, ayahuasca ceremonies have become increasingly popular in the West.

How Is Ayahuasca Made

Ayahuasca is most commonly brewed from two plants, although over 80 different medicinal plants are traditionally added admixtures in various indigenous recipes. [2] Depending on the intention of the shaman, a wide variety of ally plants, such as Mimosa hostilis, Brugmansia / Toé, or mapacho (tobacco) may be added. The two standard ingredients present in most preparations, however, are:

- The vine Banisteriopsis caapi, also known by the names yagé or aya waska. Although not very psychoactive on its own, according to indigenous perspectives, the vine is where the spiritual potential and healing power of ayahuasca actually lie.

- The leaves of Psychotria viridis, also known as chacruna (meaning “mix”), or Diplopterys cabrerana, known as chaliponga or chagropanga. The DMT contained in these plants needs the vine in order to become psychoactive when taken orally. However, some indigenous perspectives view the effects of DMT admixtures as if they only “illuminate” the visions that the vine already holds within, and some as a distraction from the actual healing process.

The ayahuasca brewing process takes many hours and requires patience and care. A basic recipe goes as follows:

- B. caapi is cut into small chunks, washed, and then pounded with a mallet in order to break apart the veins of the vine.

- The bark is stripped and placed into a cauldron or pot.

- This layer is covered with P. viridis or D. cabrerana leaves.

- The remainder of B. caapi bark is added, and then another layer of P. viridis or D. cabrerana.

- Water is added, and the brew is simmered on low heat for about 6h with occasional stirring.

- After that, the liquid is strained, and then further filtered through a cloth.

- The clear liquid is reduced (simmered) until the desired consistency is achieved. This should take about 3h.

The end result is a dense, dark, and bitter brew with the combined healing properties of the vine and psychoactive properties of the leaves.

While a standalone B. caapi tea would still be called ayahuasca, a standalone DMT-containing chacruna tea would not. Although its symbiosis with DMT-containing plants is very unique, the diversity of ayahuasca brews makes it so much more than liquid DMT.

The Ayahuasca Experience

Ayahuasca ceremonies are usually held in a traditional round wooden cabin called maloca. The participants are set up in a circle, at a comfortable distance from one another, beside the walls of the ceremony space. Futons and buckets for purging are a couple of the essentials normally provided in any ceremony.

The shaman normally sits at the head of the circle, opposite to the entrance of the maloca. You may have met them before in regular clothing, but during the ceremony they will commonly wear traditional garments and accessories belonging to their culture. They will also normally wield a chakapa—a bundle of dry leaves used for performing cleansings and as rhythmical accompaniment while chanting sacred shamanic songs, icaros.

It’s not uncommon to see an altar with items of special spiritual value in the ceremony space. You are normally welcome to bring something small and personally meaningful and contribute to it.

Before drinking, the shaman usually performs one or a few cleansing/preparatory rituals. These often involve the use of traditional tobacco, whose smoke the shaman either blows over the ceremony participants (soplando) while shaking the chakapa. Blowing a powdered tobacco mix called rapé through the participants’ nostrils with a blowpipe is also common.

Once the cleansings are finished, the brew is served to each participant; then the lights are dimmed and the effects are awaited in silence.

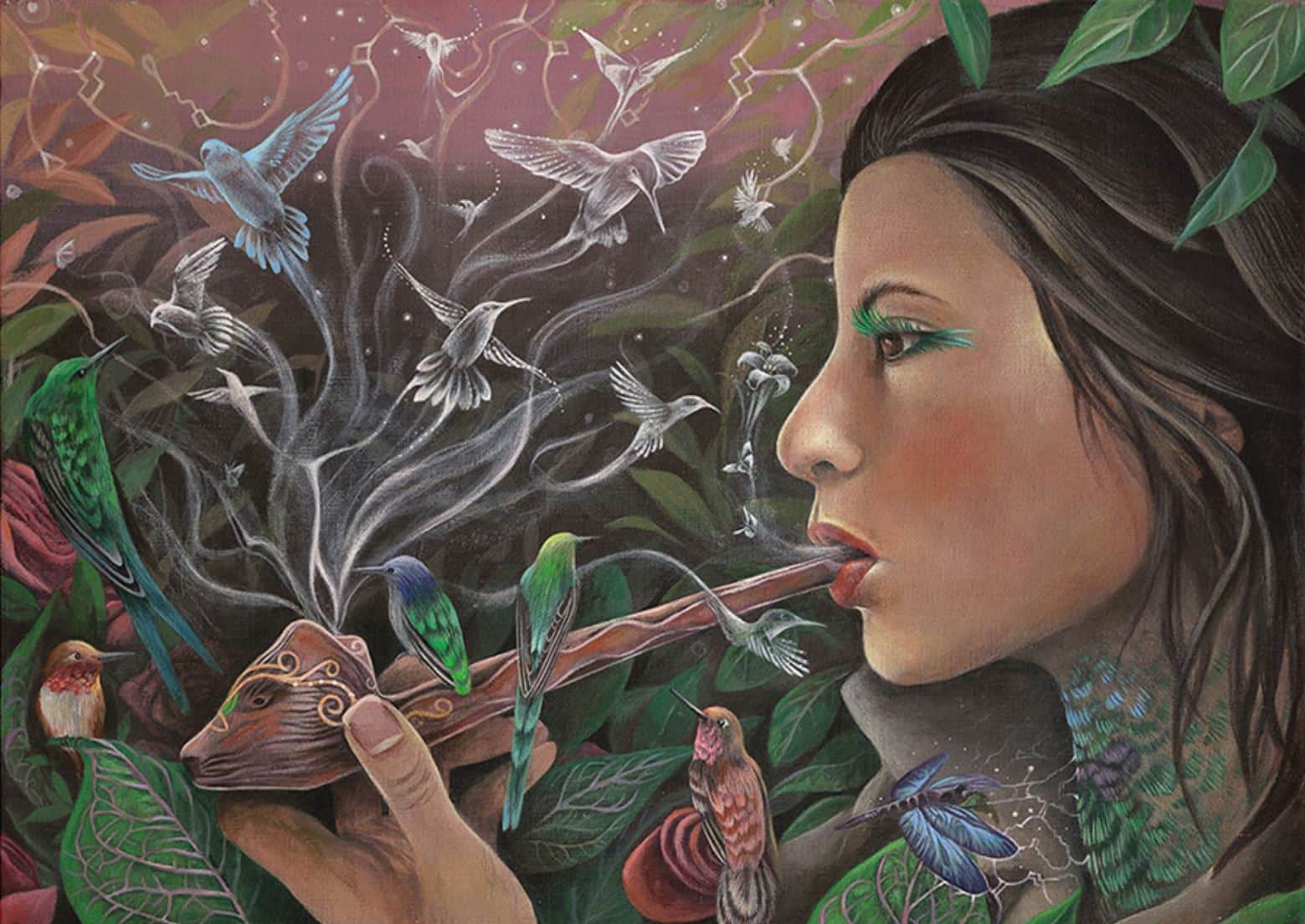

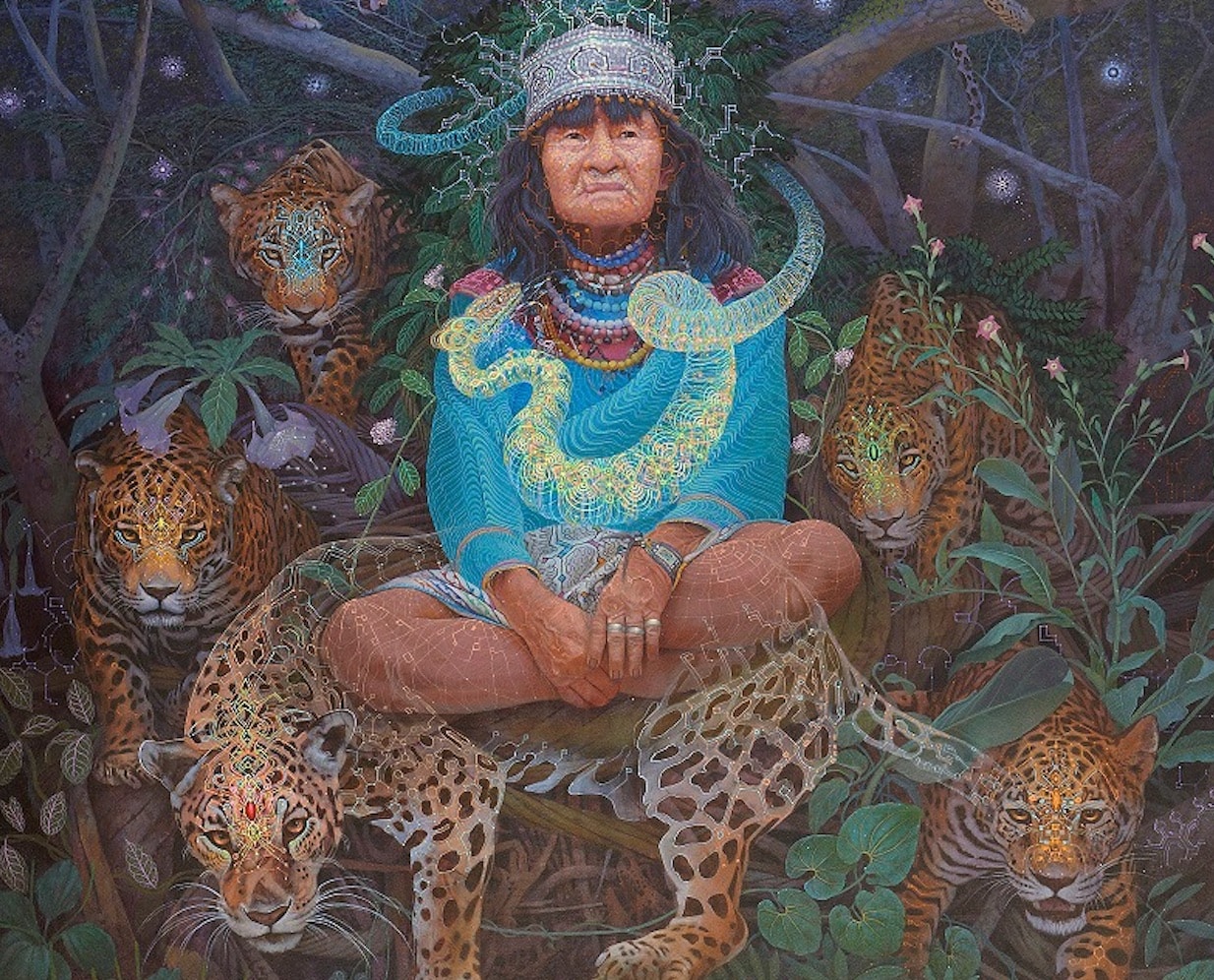

Artist credit: Fabián Jimenez - Blissful Awareness

As the group braces for the coming journey, many sounds will start echoing throughout the maloca. Purging is often the early indicator that the brew has reached its first stop, and that the active compounds in the vine are producing nausea in the stomach. It is soon followed by various perceptual changes, visions, emotions, and insight.

Many of the participants will also feel emotional release at different times. The emotions coming up may fill the maloca with moans of pleasure, childlike laughter, sobs of sorrow, or sighs of remorse. All of these can also be looked at as energetic packages projected into the ceremony space by the drinkers, and they all build the collective energetic landscape that the shaman’s job is to manage.

Throughout the ceremony, and depending on how many people there are and what energies are manifested, the shaman has more or less spiritual work to do. Their main task is to set up and defend the safe space and to act as a channel of communication with the spirit world.

They accomplish both by singing icaros; these powerful melodies are relayed to them in real time by their plant spirit allies and they serve to manage and transform the energetic landscape within the ceremony space. If a participant is in need of a shaman’s assistance, the properly trained curandero should be able to apply a variety of shamanic healing techniques to alleviate or dispel the malevolent experience.

After some hours, as the effects are starting to wear off, the shaman usually performs a closing healing ritual in which they “suck out” (chupando) the remaining negative energies.

This account is just a rough and generalized portrayal of how a typical ayahuasca ceremony plays out in certain indigenous and mestizo shamanic healing contexts throughout Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. Many mestizo and some indigenous ceremonies are also imbued with elements of Christianity, while ceremonies in Brazil are more social, involving song and dance rituals and serving more for strengthening communal identity than for healing. [3]

Common (“traditional”) themes across the landscape of ayahuasca ceremonies include: the central role of the shaman, the singing of icaros, chants, the use of additional plant medicines such as rapé (sacred tobacco snuff), and the use of energy healing techniques.

But the ayahuasca healing tradition is constantly changing and evolving as well. Neoshamanism has introduced novel elements to contemporary shamanic ceremonies just like Christianity influenced older healing traditions.

Ayahuasca Effects

Ayahuasca effects usually take between 20min and one hour to start manifesting. The initial feelings that arise after drinking are difficult to put in words, but they can be described as an awareness of a changing state of consciousness, which may be amplified by some anxiety or simply the realization that there is an impending journey with no going back.

From this diffuse array of sensations, a distinct feeling of nausea arises early on. Some participants get the need to purge right away, some are prompted by the sounds of others purging, some hold on and purge during another wave of nausea, and some don’t purge at all.

Purging

Purging with ayahuasca likely seems daunting to many who haven’t experienced it, but it’s a natural process that helps clear out some of the toxins from the body and leaves the drinker feeling much better. Some indigenous communities consider it the main purpose of drinking ayahuasca, calling the brew itself ‘La Purga’ and swearing by this process as one that rids the body of toxins and negative energies.

Visions

Soft and ungraspable visions should start to emerge behind closed eyelids. Like with other psychedelics, they commonly react to sounds and noises in the environment, creating synesthesia, an effect of connected senses in the drinker. The visions tend to solidify in each wave, eventually resulting in a display of otherworldly landscapes and spiritual entities which do not appear to be influenced by outside noises anymore, suggesting that they may in fact exist independently of our reality.

Not everyone sees visions, and not everyone who sees visions sees other worlds and entities. Although they truly are one of the main delights of drinking ayahuasca, they should not be treated as the purpose or goal of the ceremony. You should focus on self-healing and insight rather than on the visions, and be okay with whatever you see or don’t see. Resenting the brew or the shaman or any other factor for not getting the intensity of visions you were expecting can easily lead to a negative experience next time around.

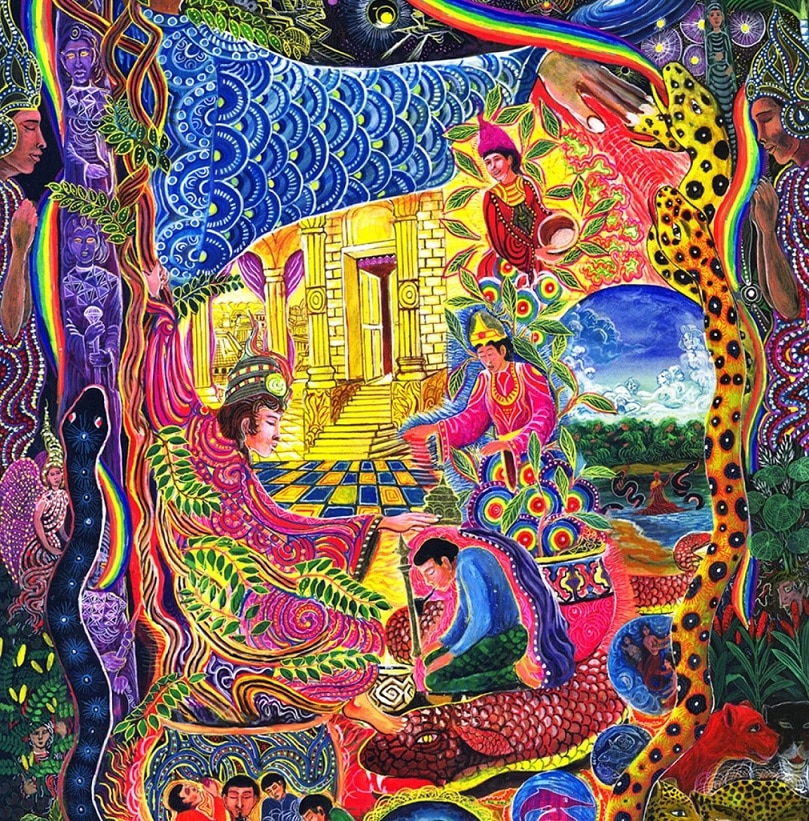

Artist credit: Chris Dyer - The Purge

Spiritual Effects

Ayahuasca can open up a wide array of thoughts and emotions for you to explore. You may see repressed memories, previous lives, have realizations of your dysfunctional patterns of thought and behavior, gain deep insights into the nature of life, love, and the universe. You may feel things you’d never felt before in intensities you had no idea were possible, and experience releases of bottled up emotions that may clear the path to your psychological growth and well-being.

Find out here what are The Spiritual Benefits of Microdosing with Ayahuasca Vine

Ego Death

The "holy grail" of ayahuasca journeys, and something you may have read about or had some experience with while using other psychedelics, is attaining ego death. This means reaching a state of dissolution of all aspects of your personality and coming face to face with your own mortality. This is a scary process, but it’s one from which your ego can be reborn and after which you get another chance to mold it into a better-functioning unit which serves you rather than sabotages you.

Insight

Ayahuasca is really good at pointing out what you’re doing wrong in life. As many drinkers can attest, it mercilessly finds all of your flaws, no matter how much effort you put into hiding them from yourself. They are presented to you in an objective manner, without judgment but with a clear sense that you need to do better. You are advised to see these flaws with an open heart, embrace them, and ask for advice on how to improve. Otherwise, if you resist and defend, ayahuasca may stop playing nice and take you to some dark corners of your subconscious.

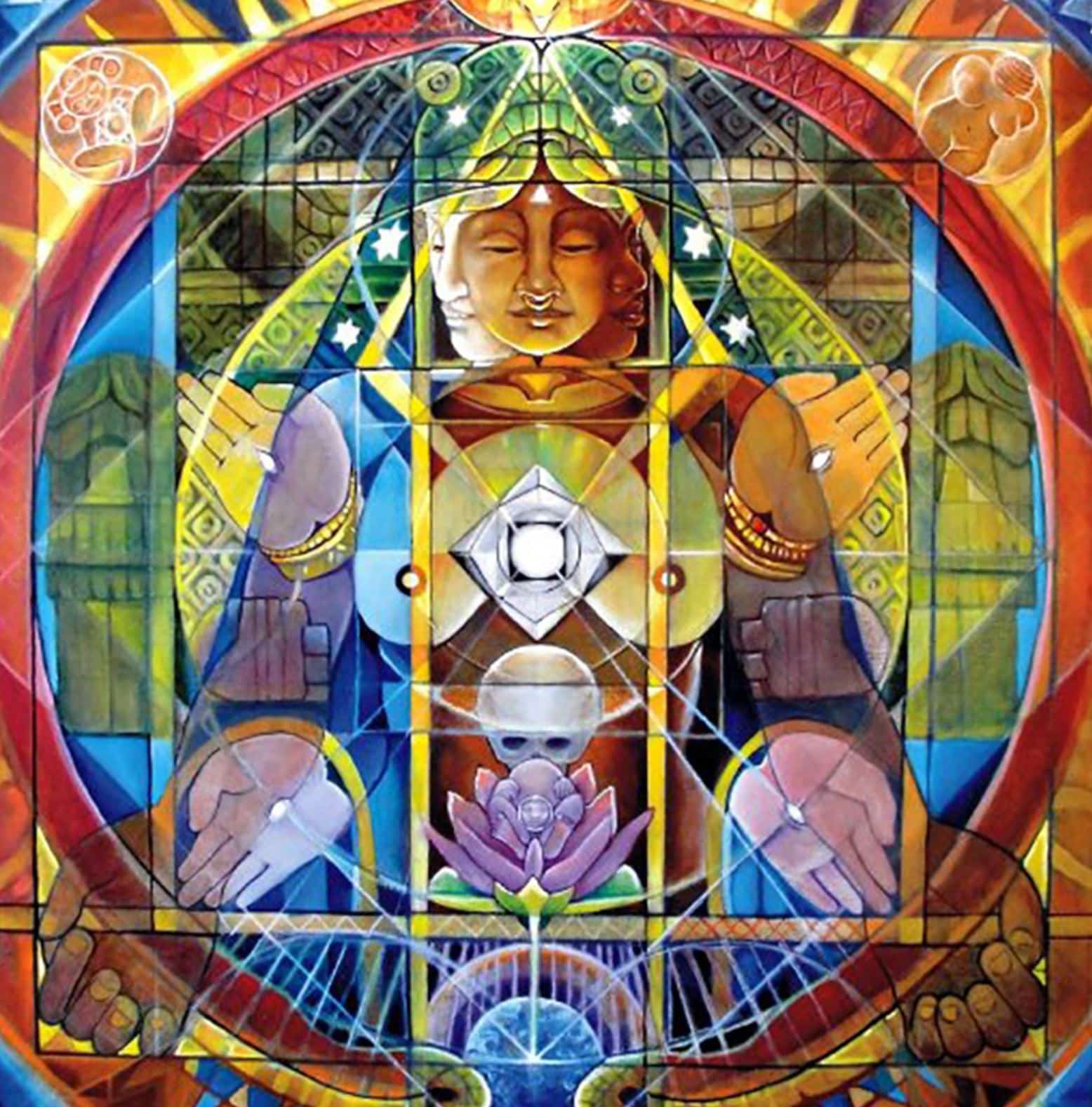

Artist credit: Carolina Maggio - Ho'oponopono

Throughout the journey, you should experience several waves of increasing nausea, visions, and insight. The deeper insight phases usually follow the vision phases, as the visions are often too distracting to focus on gaining self-realizations. Some nausea should be present throughout the journey, but intense nausea and purging often coincide with the ramping up in vision intensity.

The icaros the shaman sings act in many ways, most notably as blueprints for visionary realities and as safety nets. If done properly, singing to and from the spirits can open up tremendous ineffable landscapes for you to explore, and, should you wander off a bit too far, just listen to the icaro and it may help you trace your way back.

Letting Go with Ayahuasca

You will probably encounter shocking, unpleasant, or disturbing sensations and thoughts during the ayahuasca experience. That is natural: most of us are not accustomed to coming into such close contact with profound spirit medicines, and it is unusual for people to have a purely comfortable experience.

The key to not letting the intense or negative parts of the experience overwhelm you is letting go. Being able to release control and trust that you will be looked after.

This isn’t to say that you should be able to conquer your fear of the situation. Fear is a natural response to intense experiences and, in the words of Terence McKenna:

“[The fear] marks the experience as existentially authentic. [...] A touch of terror gives the stamp of validity to the experience because it means, ‘This is real.’ We are in the balance. We read the literature, we know the maximum doses, and so on. But nevertheless, so great is one’s faith in the mind that when one is out in it one comes to feel that the rules of pharmacology do not really apply and that control of existence on that plane is really a matter of focus of will and good luck.” [4]

So, it is expected for you to feel fear when you are thrown out of your normal framework of understanding, because suddenly all that solid ground under your feet becomes a vast drop to somewhere completely unknown.

Artist credit: Anderson Debernardi - Toé Dreams Icarus

Being able to accept this new and scary situation is important. Rather than flailing around and scrambling for some essence of solidity in the void beneath you, remember that this is a natural part of the ayahuasca experience, and what will help you is to let go. Accept the fear, accept this scary new reality, and let it happen to you.

Remember that you are being looked after, you are safe; and embrace the pains and joys of the experience. Many people recommend giving up your sense of self to ayahuasca, and remembering that she knows best. Take every lesson she gives you with humility and openness.

Once the effects begin to subside, take notice of your surroundings, and the ways in which you feel you have changed. Your shaman should perform some cleansing rituals with you, to close the ceremony in a gentle and careful manner. When everything is finished, your body and mind should be feeling a bit overwhelmed, but exhausted and ready for deep rest with vivid dreams.

Pharmacology

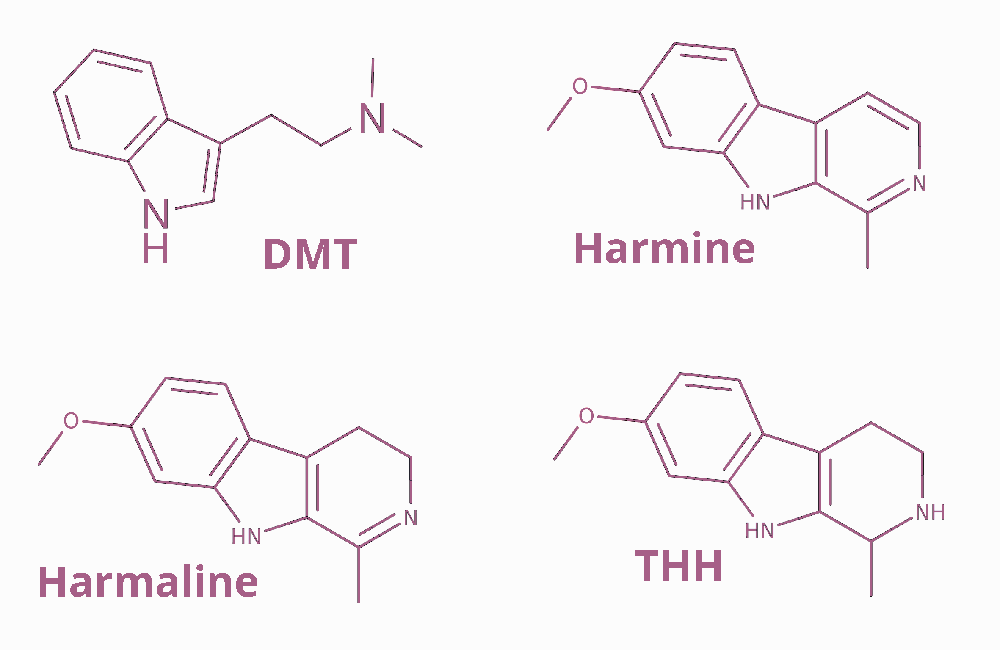

The B. caapi vine contains β-carboline alkaloids harmine, harmaline, and THH, while the DMT comes from the leaves of the P. viridis or D. cabrerana plant. Harmine and harmaline are monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), which prevent the DMT from being destroyed by monoamine oxidase enzymes in the stomach when it is taken orally.

The inhibition that harmine and harmaline do allows the DMT to enter the bloodstream intact, reach the brain, and start influencing its chemistry [5]. Both DMT and THH (the third alkaloid in B. caapi) have psychoactive effects, although DMT’s are, of course, much more intense.

In the brain, DMT primarily activates the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor. This is the same receptor that other classic psychedelics, such as LSD and psilocybin, activate. The stimulation of this receptor changes the levels of serotonin in the brain and has been connected by scientific research to some of the perceptual effects you might experience during an ayahuasca trip. These include audio-visual hallucinations, changes in the perception of time, revisiting past memories, and losing your sense of self. [5]

THH also affects serotonin, but less so than DMT. It contributes to an increase in serotonin levels in the brain, which we know can have a psychedelic effect. [6] It’s likely that THH is an important part of the psychoactivity of ayahuasca, especially considering many traditional brews are made with the vine only and without DMT-containing admixtures.

Harmine and harmaline have been shown to affect the dopaminergic system in the brain, which perhaps contributes to the anti-addictive properties of ayahuasca. They also have their own effects on the serotonin system. [7]

Because monoamine oxidase enzymes break down more than just DMT, harmine and harmaline will affect many bodily functions. As well as not being able to break down DMT, you will struggle to digest other substances in your food; this can lead to nausea. It’s therefore recommended to avoid foods containing tyramine (such as cheese, meats, caffeine and beans) before drinking ayahuasca. You should also avoid certain serotonergic medications or drugs, such as amphetamines and MDMA. [8] It’s theoretically possible to overload your serotonergic system by mixing substances with ayahuasca. More on these restrictions later.

Benefits

The potential benefits of ayahuasca are numerous, not only for those with some psychological and physiological disorders, but also for healthy people. We will discuss the science in more detail in next sections of this guide, but we will highlight the main findings here.

Recent scientific studies have shown that ayahuasca may be effective in the treatment of addiction, [9] depression, [10] anxiety, [11] and eating disorders. [12] There is also reasonable scientific assumption that the brew’s effects may help those suffering from PTSD, [13] as many personal accounts available online can attest to. It’s assumed that the profound insight ayahuasca journeys can bring, if properly integrated, can lead the individual to understanding the root of their problem and realizing ways in which they may break the dysfunctional patterns of thinking and behaving and replace them with new, more healthy ones.

The alkaloids in ayahuasca have also been found to have antiparasitic [14] and antimicrobial [15] functions, confirming indigenous beliefs about the healing aspect of purging. Ayahuasca has for a long time been used as a traditional medicine to help people suffering from various infections and inflammations. [16]

Finally, for those not suffering with illnesses, ayahuasca’s spiritual effects can amount to life-changing realizations catalyzing psychological wellness and spiritual growth. As the use of ayahuasca becomes more mainstream, it may become an accepted tool in psychedelic therapy, as well as personal development.

Risks

Ayahuasca is a relatively safe substance, but there are some risks you should consider before the journey.

Although it’s best to avoid mixing any strong medications with the brew, there are several confirmed dangerous drug interactions with ayahuasca. Here are some substances that you should take extra care with:

- SSRI medications. Any medication that has an effect on the serotonin system, including Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), has the theoretical potential to induce serotonin syndrome when mixed with serotonergic psychedelics like ayahuasca. Despite there being no recorded deaths from mixing SSRIs with ayahuasca, and many people reporting successfully combining the two, we recommend caution. It’s also important to balance the risks of suspending your medication with the potential risk of an unpleasant interaction. Common SSRIs include Celexa, Lexapro, Prozac, and Zoloft.

- MAOI medications. Some medications contain MAOIs, the same substance found in the ayahuasca brew. Mixing MAOIs with ayahuasca is known to cause dangerous side effects such as severe liver and kidney impairment, severe or frequent headache, uncontrolled hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases. [8] You should safely suspend your MAOI medication before taking ayahuasca. Common MAOIs include Emsam, Marplan, Nardil, and Parnate.

- Brugmansia/Toé. This is a flowering shrub from the nightshade family. Also known as “angel’s trumpet,” it is recognized by its large, golden trumpet-shaped flowers. Some ayahuasca shamans will put toé in their ayahuasca brew. Excessive use of Toé can cause permanent mental impairment. Deaths can occur from miscalculated dosages.

- 5-MeO-DMT & Bufo alvarius toad venom. The practice of smoking the secretions of the Sonoran Desert Toad, or Bufo alvarius, has recently entered shamanic circles. The secretions contain more than a dozen tryptamine compounds, the most important of which are bufotenin and 5-MeO-DMT, which may have contraindications with the harmala alkaloids in ayahuasca. At least two deaths have been recorded in the medical literature where harmaline and 5-MeO-DMT were found in autopsies. [17]

- Cardiovascular medication. Ayahuasca raises blood pressure and heart rate [18] and drinking it with any cardiovascular medication (or substance that affects this system), and especially those used to manage hypertension, can be dangerous and even fatal.

- Lithium. Sometimes given in combination with some forms of medication. Numerous reports suggest that lithium can cause fatal seizures and heart attacks when mixed with psychedelics like ayahuasca. [19] Do not take ayahuasca if you are prescribed lithium.

- Tramadol. This is a powerful synthetic opioid that can cause seizures when mixed with certain psychedelics, including DMT. Do not take tramadol at the same time as ayahuasca.

- Antipsychotic medication. Ayahuasca should not be used by anyone who suffers from psychosis and is taking antipsychotic medication. Ayahuasca or DMT can be dangerous to those personally afflicted by, or with a family history of psychosis. [20] Latent (not yet detected) psychosis can also be triggered under the effect of the brew.

Along with the physical risks, it’s important to be aware of the fact that there are psychological risks involved with any psychedelic experience. Having your perceptions and thoughts radically altered can be intense and overwhelming. It is common for people to experience fear and distress during an ayahuasca ceremony. An experienced shaman or facilitator and a secure support system should help contain or release these emotions and bring you back to spiritual safety.

If you’ve had a distressing experience, practicing proper integration techniques with knowledgeable facilitators can help you avoid enduring long-term psychological harm and will likely help you gain insights into where the dark episode came from. This will ultimately enable you to grow from it and see the journey in a positive light. Read more about integration in the coming sections.

Learn the most important 3 Questions to Ask Your Ayahuasca Shaman or Facilitator.

Part 2:

Healing

Whether you are from the Amazon or Los Angeles, tea drinkers from all walks of life, cultures, and nationalities often find the ayahuasca experience to be profoundly healing, often in unexpected ways.

But why is ayahuasca so healing, and how exactly does the plant medicine heal?

In this chapter we'll take a look at the Amazonian paradigm of illness and healing, as well as recent scientific research into the therapeutic benefits of ayahuasca.

Amazonian Medicine

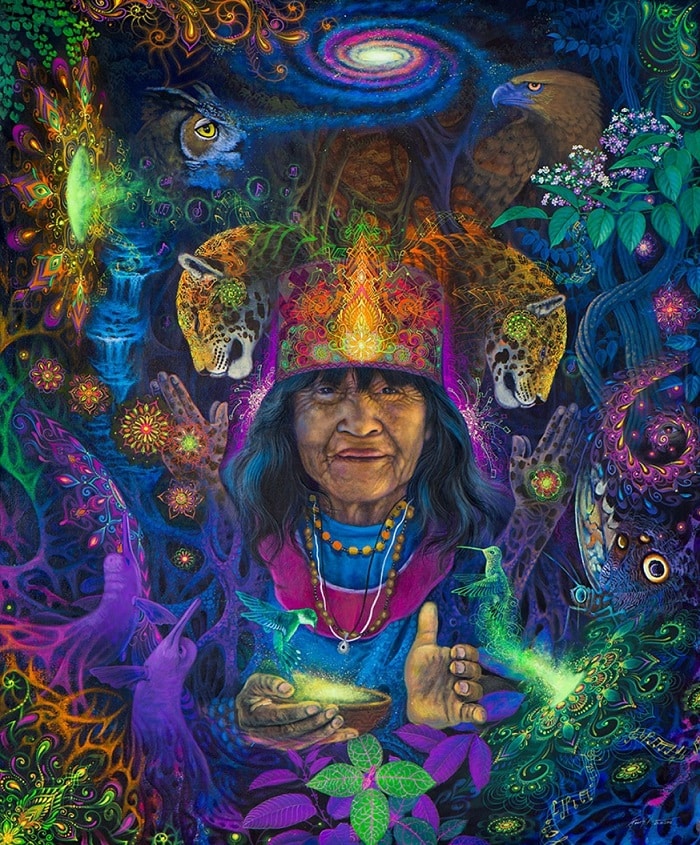

In Amazonian cultures, plant medicine healers have a different view of illness and disease, as well as a different view of Nature. Nature is perceived to be sacred, a divine teacher Herself, who is home to many more divine teachers. Ayahuasca is considered to be a Master Plant Teacher, one of many. To take ayahuasca is to enter into a spiritual school, that will shine a light on that which you cannot see or will not see, to show you what you need to heal in order to become the best human you were meant to be. In the Amazon, the power of the plant medicine comes from the consciousness of the Teacher plant Herself.

Artist credit: Felix Pinchi Aguirre - Mother Medicine

While ayahuasca by itself can be considered to be deeply healing, the skill of the shaman administering the ayahuasca can also profoundly impact the depth of healing experienced by a ceremony participant. This includes the shaman’s ability to extract illness, move energy, invoke the assistance of the plant allies they have cultivated through dieta, and call in helping spirits; as well as prescribe supporting plant remedies, herbal baths, and other shamanic practices outside of ceremony.

To be a knowledgeable and skilled shaman, one must have clocked serious solitary dieta time with a range of plants. Potential shamans must spend months fasting and communing with the brew, and must resist the urge to use the spirit of ayahuasca for sorcery. If completed successfully, the shaman will emerge from their training with an understanding of how to use the spiritual power of ayahuasca for healing.

In addition to knowing how to identify these plants in the forest and prepare plant remedies, the shaman would have also needed to receive the song or icaro of that plant. The number of songs the shaman has received is also an indicator of mastery, the more “power” they have. Learning the songs of another doesn’t carry the same power as having “received your own songs from the vine.”

The shaman would need to know how to raise and lower the energetic frequency of a ceremony, through song or prayer. They would need to be able to successfully invoke the assistance of plant allies, helping spirits, divine beings, elemental forces and animal guides.

To understand more about how Amazonian healing works, check out this article: What Are Ayahuasca Icaros & How Do They Work?

Scientific Research

Current scientific studies are complementing shamanic knowledge of the healing potential of ayahuasca and its ability to treat a range of mental issues. Here we will cover some of the most notable research done so far.

Addiction

A study of Brazilian adolescents who regularly used ayahuasca found that they were less likely to use alcohol than non-ayahuasca users, [21] and a preliminary observational study has shown that people with problematic substance use (dependence or addiction) found significant reductions in cravings after a single ayahuasca retreat. [22]

Another observational paper outlined the success of several months of ayahuasca treatments in combination with psychological therapy and communal living in Takiwasi, a retreat center in Peru. [23] The author claims that the combined therapy has improved or extinguished addiction in 62% of the center’s patients.

Eating Disorders

Ayahuasca has been explored as a potential treatment for eating disorders, with many accounts surfacing of people who have recovered from severe eating disorders thanks to profound ayahuasca experiences. [12]

Depression

Ayahuasca has also appeared in the scientific literature as a potential treatment for the most severe (treatment-resistant) cases of depression.

One preliminary report found that a single dose of ayahuasca had a significant healing benefit for patients in a psychiatric unit who were experiencing depression. [24]

Two years later, a randomized placebo-controlled trial of thirty-five patients confirmed that ayahuasca could effectively treat severe depression. [25] The same team conducted another study two more years after, which was published in the prestigious journal Psychological Medicine, and which again reported rapid and sustained antidepressant effects for people with severe, treatment-resistant depression. [10]

You might be interested in learning more about whether Ayahuasca Can Heal Depression.

Anxiety

Research conducted on members of the Santo Daime church, a Brazilian syncretic religion which uses ayahuasca for ritual purposes, found that panic-like anxiety and hopelessness decrease an hour after ingesting the tea and remain lower after the ceremony. [11]

PTSD

A number of personal reports have surfaced on the potential of ayahuasca to help those suffering from PTSD. Although no official study has been conducted yet, some strong arguments for taking this effect seriously have recently been laid out. [13]

The effectiveness of ayahuasca in treating these conditions is partly due to its biochemical interaction with the brain and partly due to the profound spiritual experience that it induces. Research has shown that the magnitude of the spiritual experience that accompanies a psychedelic trip is directly related to the healing benefits. [26] Therefore, the set and setting of an ayahuasca experience, and the ability of the facilitators to induce and guide a spiritual journey, is key to unlocking its therapeutic properties.

Therapeutic Uses

Ayahuasca retreats are becoming popular with people of all ages who are looking to heal some internal turmoil, make peace with repressed emotions, uncover and release past pains, gain clarity, direction, and inspiration in life, and, in general, attain ego dissolution and spiritual growth.

Ayahuasca can be used therapeutically in various ways, but its current illegality presents an obstacle for many who wish to attend a ceremony. These soul-seekers are faced with a choice of either traveling to the Amazon rainforest (or elsewhere where the brew is legal or “not illegal” such as Costa Rica) and drinking within a retreat center context or seeking out local, often underground ceremonies offered either by traveling shamans from the Amazon or Westerner facilitators with varying degrees of experience and skill.

This is why would-be ceremony participants sometimes resort to recreating the ayahuasca experience at home through mixing ingredients which mimic the chemical properties of the brew itself. These self-healing concoctions are referred to as anahuasca or pharmahuasca, depending on the base ingredient, which can be an extract of B. caapi (former) or a chemical analog plant such as Syrian rue or Mimosa hostilis, a pharmaceutical MAOI such as Moclobemide, or an extract of one or several β-carboline alkaloids (latter). The second ingredient is usually freebase DMT extracted from any of the number of plants that contain it.

Artist credit: Li Lian Kolster - Medicine Birds

Making ayahuasca analogues is not recommended for first-timers or those without adequate prior experience with psychedelics. Even then, it’s always advised to have a sober sitter present due to the potential risks involved, which we’ve already discussed.

In any context of using ayahuasca therapeutically, a ritualistic setting and an experienced guide/shaman/facilitator are highly recommended to get the most out of the experience. It is true that the ayahuasca journey is ultimately an internal path only you can walk, but starting off on the right foot, so to say, and having the path laid out more clearly and protected by an elder, powerful healer can make a world of difference.

Additionally, the therapeutic journey with ayahuasca only begins with the ceremony. During that experience, you may find out what you’re doing wrong in life and gain some understanding of how to approach fixing it. However, the actual work you need to put in goes way beyond just acknowledging your faults. The insights need to be properly integrated into daily life and everyday effort is needed to apply what you learned in your journey; this is what can truly make the difference between a momentary revelation and sustained spiritual growth.

For many people, the time just after their first ayahuasca experience feels like a new beginning. The world may feel refreshed, or you may feel as if some of your demons or troubles have been exposed and cleansed. You may have been given a new purpose in life; or perhaps just reminded of the one you’ve always had.

In many ways, ayahuasca puts you at the start of a long road. There will always be so much more to learn, so many more ways to change, and so much more healing to do.

Part 3:

Culture

Ayahuasca culture is rich and diverse. If you wish to experience ayahuasca, it's beneficial to understand a little bit about the history and how it has influenced both Amazonian and New Age culture.

From inspiring an emerging genre of visionary art, to influencing folk music and electronic trance, the creative legacy of ayahuasca carries its own healing powers.

Unsurprisingly, ayahuasca is increasingly being embraced by personal development aficionados and entrepreneurs seeking creative inspiration.

What was once an obscure, psychoactive and highly purgative herbal remedy drunk by indigenous tribes and mestizo communities in the Amazon, ayahuasca is now the “Drug of Choice for the Age of Kale.”

Early History

Ayahuasca has been used for ceremonial, medicinal and spiritual purposes by the indigenous tribes in the Upper Amazon for many generations, and, possibly, for hundreds or thousands of years. In many traditional practices, such as those performed by the Shipibo people, the shaman is the only person who drinks ayahuasca. The participant relies on the shaman to bring back divine wisdom from the encounter, which will help treat their condition or give them spiritual advice. [27]

Indigenous activist Daiara Tukano describes the role of ayahuasca in South American indigenous cultures:

“[Ayahuasca] is found in origin histories for all our peoples. For our civilizations, the sacred medicine has been the source of our knowledge, identity, and culture since the creation of the first person. Consequently, it is always present in our songs and histories, as well as being part of the ancient relations between our peoples.” [28]

Unlike with other psychedelics with ancient use, it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly or even approximately when ayahuasca use started. This is due to the fact that it’s a liquid rather than a powder, so its remains on artefacts are not as available for chemical analysis. It’s not possible to say without doubt if a ceremonial drinking container, such as the 2,000 year-old Quito Bowl, was used for serving ayahuasca or something else. [29]

The subsequent reports provided by Pablo Maroni in 1737 and Franz Xavier Veigl in 1755 spoke a bit more favorably about the brew and the ceremonies, with the latter account even referring to as “a plant worth mentioning” even though it was used “only for superstitious practices and witchcraft.” Still, ayahuasca didn’t receive interest for one more century because all these records were originally written in Latin and sent only to Rome, so their audience wasn’t large and they got buried away in the archives.

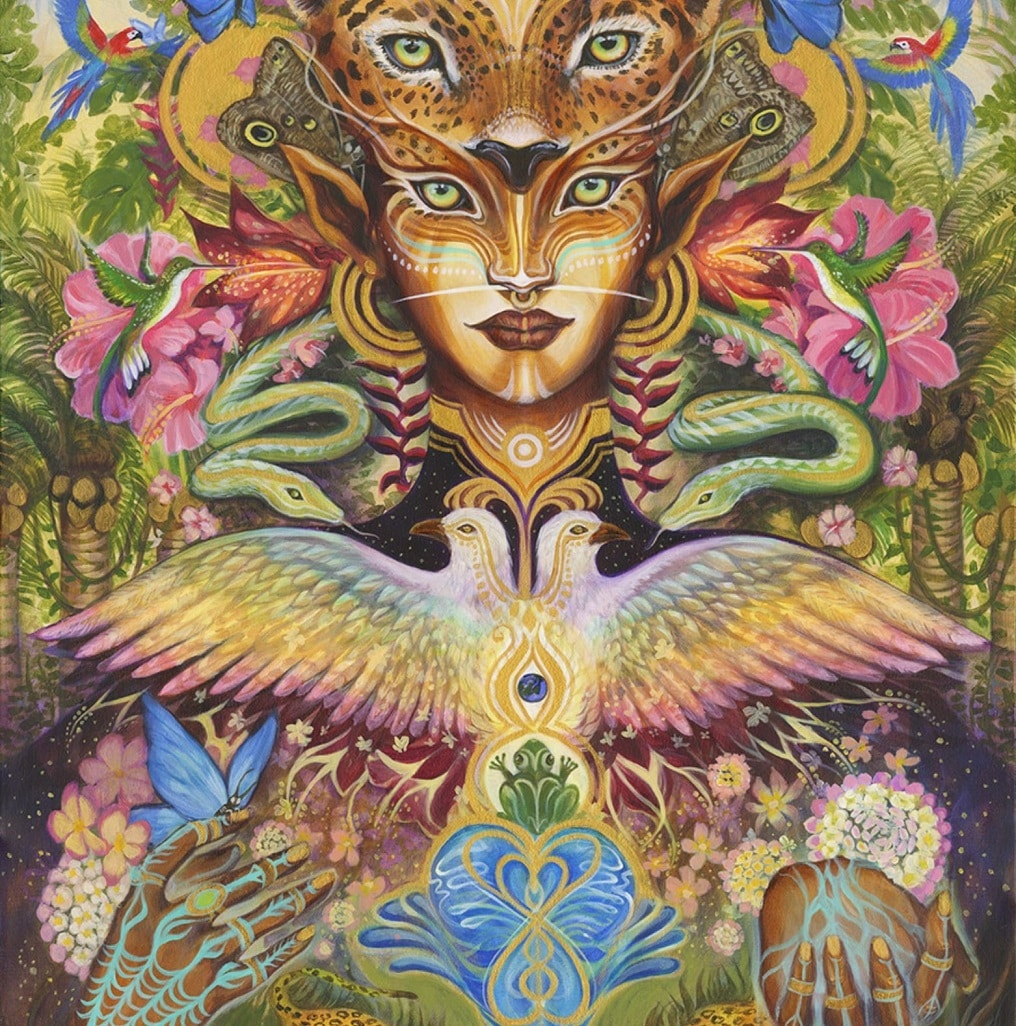

Artist credit: Jorge Enrique Ramirez Flores - Mama Sacha

Chemical analysis of a 1000-year-old shamanic pouch found in Bolivia showed traces of harmine and DMT, elements contained in the ayahuasca brew. [30] This finding is often used to attribute ancience to ayahuasca use, but it’s more probable that this particular shaman was carrying some yopo (Adenanthera peregrina) powder rather than ayahuasca plants in his medicine bag. Yopo contains the same compounds and its powder has been used as a ritualistic snuff for a long time in the Amazon. [29]

The earliest accounts in modern history we have of the word “ayahuasca” come from the Jesuit priests who entered the Amazon rainforest in the second half of the 17th century. [31] These early missionaries did not report favorably on the use of the potion, calling it “diabolical” and describing the divination ceremonies as witchcraft and sorcery. Naturally, the use of ayahuasca was suppressed by the colonists due to its unchristian nature.

The subsequent reports provided by Pablo Maroni in 1737 and Franz Xavier Veigl in 1755 [32] spoke a bit more favorably about the brew and the ceremonies, with the latter account even referring to B. caapi as “a plant worth mentioning” even though it was used “only for superstitious practices and witchcraft.” Still, ayahuasca didn’t receive interest for one more century because all these records were originally written in Latin and sent only to Rome, so their audience wasn’t large and they got buried away in the archives.

Revival

Eventually, the exploitative rubber-tapping industry in the Amazonia brought a larger number of European colonists into contact with ayahuasca for the first time, potentially contributing to its spread throughout South American countries in the late 1800s. [33] Although the indigenous peoples were decimated by the rubber barons, they would be moved around throughout the whole Amazon region and ayahuasca ceremonies were held as one of the few means of healing available.

Eventually, in Brazil, this set the stage for the formation of the Santo Daime and União do Vegetal (UDV) religions, which further boosted the popularity of ayahuasca in South America. [34] The newly-formed religions incorporated elements of Christian belief into some ayahuasca practices, likely as a means of gaining favor with the oppressors.

Throughout the 19th century, a wave of ethnobotanists came into contact with ayahuasca, but none of them wrote in great detail about the vine, the brew, nor the ceremonies. Richard Spruce was the first to collect specimens and catalog the plant scientifically, as well as the first one to provide a detailed, firsthand account of the effects of the brew and the ayahuasca ceremony context [35].

It wasn’t until the 1960s that ayahuasca was truly brought into the Global North’s awareness by anthropologists and ethnobotanists, foremost among them the Harvard professor Richard Evans Schultes. [32] Carried by the counterculture movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s, ayahuasca was popularized by psychedelic figures such as Terence McKenna, who often emphasized the DMT in the brew as the primary cause of its psychoactive power.

Contemporary Ayahuasca Shamanism

The ayahuasca ceremony that a typical Westerner might encounter today can be very far removed from the original, traditional ayahuasca ceremonies. Not only is there wide variation in the kinds of ayahuasca shamanism among indigenous communities, but modern ceremonies may also differ from traditional practices. [27]

For example, it’s rare to see group ayahuasca ceremonies in many traditional contexts. While some indigenous cultures do indeed use ayahuasca for social bonding (usually with little or no DMT), it is much more common for shamans to have one-on-one healing ceremonies with their patients, with the patients rarely drinking themselves. Instead, the shaman uses their spiritual knowledge and the visionary assistance of the ayahuasca medicine to diagnose illnesses and prescribe a treatment to their patient.

Even if you attend a ceremony run by an indigenous shaman, it is unlikely that you will be experiencing the cultural roots of the ayahuasca tradition. For example, in the Shipibo tradition, patients will very rarely drink ayahuasca; but contemporary Shipibo ceremonies (one of the most popular among Westerners) almost always involve large groups of people drinking the medicine themselves.

Although this is perhaps the most significant difference between traditional ayahuasca ceremonies and contemporary ceremonies, the cultural differences go much deeper.

In traditional ayahuasca shamanism, witchcraft and sorcery are important elements. Healing often involves the deflection of dark energies back to their source; and as such, traditional shamans can certainly cause harm with their knowledge, and can evoke fear among locals. These darker elements of sorcery are not present in contemporary ceremonies, and as a result many Westerners see ayahuasca through rose-tinted glasses.

Another difference is that many traditional ayahuasca ceremonies involve mixtures that don’t include DMT. However, Western customers often overemphasize the value of the DMT component, and won’t be interested in ayahuasca brews that don’t give them the visions they are after. Contemporary ceremonies will also downplay the need for other plant medicines, such as tobacco, to be included as part of the overall healing process; which is typically an important traditional role of the shaman.

Most of the indigenous peoples who use ayahuasca have a history of confrontation with European colonists, especially during the damaging rubber-tapping industry of the 1800s. They have often faced abuse, enslavement, violence, and exploitation. Preserving their traditions and culture has been a matter of survival for many generations. [28]

All this taken into account, it becomes clear that the arrival of waves of peaceful and relatively wealthy Westerners asking to experience the medicine and the visions for themselves influenced the shamans to start changing the tradition around their practices. Part of it was just the pure welcoming and sharing attitude of the locals, while part of the motivation was certainly the material gain. The latter also contributed to the emergence of a generation of money-driven charlatans who wanted to capitalize on the booming ayahuasca industry but without putting in the time and effort to go through proper shamanic training.

Artist credit: Boris Quinteros - Taita Kambo

Finally, it’s also important to make a distinction between syncretic ayahuasca churches from traditional indigenous practices. Christian-influenced churches such as Santo Daime, Barquinha, and União do Vegetal certainly have borrowed from traditional ayahuasca shamanism, but are modern religions and should not be considered traditional. Part of their search for legitimacy involved the adoption of Christian themes, which are viewed as colonialist by some indigenous peoples. [28] Meanwhile, many of the mestizo (and some indigenous) shamanism practices in the Andean countries also integrated elements from Christianity in their practices.

As well as all the above styles of ayahuasca ceremony, neo-shamanic ceremonies held without any traditional input are seen in countries of the Global North. Here, a wide range of shamanic, mystical, new-wave, hippie, hipster, and all other kinds of “alternative” practices may be incorporated into ayahuasca ceremonies. Sometimes, the brew is not even made with traditional plant materials, but with extracts and/or analog plants and chemicals (anahuasca and pharmahuasca).

As you might expect for a brew with dozens of different names across Amazonia, there are many different ways in which ayahuasca can be prepared and provided. In many traditional recipes, and especially when used socially by the whole community, the brew would not necessarily contain DMT. Many other preparations, by and large those used by shamans for divination and healing, do include DMT-containing plants such as Psychotria viridis or Diplopterys cabrerana alongside the traditional B. caapi.

As well as using different plants, different traditions involve unique recipes and quantities. The Santo Daime religion, for example, involves a rigorous and precise brewing process lasting many days, that produces brews of varying degrees of strength. [36]

Ayahuasca is also viewed through a different spiritual lens depending on the tradition. For example, groups that brew yagé in Colombia commonly view the ayahuasca spirit as being masculine, whereas most other Amazonian traditions consider it to be feminine. [36] For the Barasana, ayahuasca helps to remind them of their role in the maintenance of nature, and the benefits they receive from being its guardian. [37] For the Ashaninka, and perhaps most indigenous peoples who use it, ayahuasca is considered to have an expansive and real consciousness, that must be treated with the respect and compassion that we would give any ancient sage. [38]

The indigenous history of ayahuasca is often overlooked in the contemporary popularity of the brew. Concerns about globalization and appropriation are frequently at the forefront of the ayahuasca conversation. Reminding ourselves of the source of the B. caapi medicine and the spiritual history of the ayahuasca brew is crucial in being able to respectfully journey with the Vine of the Spirits.

Arts

Visionary Art

Artist credit: Pablo Amaringo - Ayahuasca Chayana

While for most drinkers the ayahuasca experience and visions are difficult to verbalize or otherwise express, many artists have found ways to project their visions on a canvas, paper, or a digital background.

Pablo Amaringo is the pioneer of ayahuasca visionary art. His captivating paintings capture the essence of his ayahuasca journeys and communicate them to the world. Thanks to the encouragement and support by anthropologist and vegetalista Luis Eduardo Luna, Amaringo’s visionary work was published, bringing this aspect of journeying with the brew worldwide recognition and stoking massive interest in the realms of psychedelic visions. [39]

Amaringo taught his Neo-Amazónica style of art for many years at the Usko Ayar School in Peru, inspiring generations of artists and creating a new wave in psychedelic experience visualization. Nowadays, artists worldwide, even those who have never tried the brew, are tapping into these collective visions and inspiration and creating masterpieces of their own.

Music

Medicine Circle Music

Medicine circle music is a neo-shamanic addition to the ayahuasca ceremony. This music draws inspiration from various folk and traditional indigenous melodies, and interprets them in a creative and contemporary way. It’s usually played acoustically, on a guitar accompanied by some rhythmical instrument.

Electronic Music

Some contemporary ceremony facilitators don’t sing icaros or play an instrument. Instead, playlists consisting usually of electronic music are played during the ceremony. Genres such as psychedelic ambient and progressive downbeat have given rise to artists creating perfect music for journeying deep with ayahuasca.

Part 4:

Spirituality

Ayahuasca culture is rich and diverse. If you wish to experience ayahuasca, it's beneficial to understand a little bit about the history of ayahuasca ceremony work, and familiarize yourself with the spectrum of cultures, churches and spiritual lineages that work with ayahuasca.

That way, you can make the best choices for yourself and decide which ceremonial container feels right for you.

Bear in mind that ayahuasca culture is continuously changing and adapting to meet the needs of the communities that consume it.

Many lineages are living and evolving wisdom traditions, so that what is practiced now may be very different from how ceremonies were conducted in the last decade.

Mestizo Shamanism

Mestizo ayahuasca shamanism, often referred to as vegetalismo, encompasses shamanic healing practices which have adopted indigenous traditions and mixed them with elements of Catholicism, regardless of whether the curandero is a formal Catholic or not.

This shamanic tradition started emerging during the rubber boom era, in the late 19th century. The areas of the rainforest which had low indigenous populations saw black and mestizo (mixed descent) people brought in to tap rubber. The mestizos would, on occasion, spend long periods of time with the indigenous people, learning their healing traditions and eventually becoming curanderos for other mestizos.

Mestizo curanderismo is most commonly found in isolated rural areas, at a distance from the indigenous populations due to their ideological differences (the adoption of what the indigenous see as colonist influences from the mestizo tradition). However, in the Loreto province in Peru, home to possibly the main ayahuasca hub of South America—Iquitos—mestizo curanderismo thrives both in urban and rural communities.

While it is true that mestizo and indigenous shamanistic traditions differ, these differences are mostly subtle. The main one is probably the mestizos’ clearly polarized approach to cosmology which comes from the Catholic culture (good vs evil, God vs Satan) and which contrasts the indigenous understanding of the universe as filled with countless spirits which may be malevolent or benevolent but do not belong to distinct opposing sides of a grand cosmic war.Mostly, in New Age ayahuasca circles, various mindfulness techniques, elements from different belief systems, and divergent artistic tendencies are integrated into the ceremony. These can be anything from yoga and breathwork to bodywork and dance, to musical accompaniment which may or may not be inspired by indigenous icaros.

Music likely makes up the biggest departure from native South American ayahuasca ceremonies. Many gringo shamans do not sing icaros, but instead play folk or indigenous tunes on an instrument (typically guitar) or play a prepared playlist. As we noted, icaros are shaman’s fundamental tools; they are used for setting up and protecting a safe spiritual space, diagnosing and healing illness, vanquishing malevolent entities, and creating and guiding drinkers through spiritual realms. It’s a question whether ceremony facilitation without icaros can really be called shamanism.

An even bigger question is where these different modalities of healing work are channeled from. Icaros, for example, are “given” to the shamans by their plant spirit allies once their connection is strong enough; if one sings a song which was not “gifted” to them from the astral plains but is merely an interpretation of a local tune they heard in Peru, they aren’t so much guiding the experience as much as they are padding it with a backing track. For the ceremony participants, however, who are most often ayahuasca-naïve, this represents the full extent of ayahuasca healing they can experience.

Clearly, there is plenty of room for manipulation and pretension in these circles. That said, there are also some extremely unique and authentic novel directions the ayahuasca ceremony is being taken in by individuals who have already established themselves as strong energetic presences and purveyors of wisdom and healing coming from sources and traditions quite disparate from those of the Amazon.

The New Age of ayahuasca healing is in its infancy; it remains to be seen how the landscape will be moulded by those who take on the responsibility to wield this sacred medicine in different cultural contexts. Until then, and as always, tune in to what feels right and reject that which doesn’t. In the following sections we will talk about how best to go about assessing the safety, reliability, and authenticity of an ayahuasca ceremony, retreat, and facilitator.

Aside from this, there could be overt Catholic symbolism and imagery present in mestizo ayahuasca ceremonies. [29] Examples of this include references to various saints and Jesus, reciting of Christian prayers, the use of rosaries, Agua Florida (floral water), camphor or candles to make blessings and invoke protection.

Still, in most aspects, mestizo and indigenous traditions are similar; the Catholic influences can be seen more as addons to the indigenous practices, not their replacements. [40]

Indigenous Lineages

Brazil

Brazil was once home to a vibrant and sprawling landscape of indigenous shamanism. After the arrival of colonists, however, their use of ayahuasca was brutally suppressed, along with the decimation and enslavement of a large portion of the indigenous population.

Two variants of the brew have a long history of traditional use in Brazil: Kaapi and vinho da jurema. The former, drunk throughout most of the country, is basically the same as ayahuasca, while the latter is made from an entirely different plant, native to the brew’s home in the northern part of Brazil.

Jurema or Mimosa hostilis contains DMT but is not very psychoactive on its own, and it’s unclear whether another MAOI-containing plant was traditionally added into the brew to achieve psychoactivity.

The ritualistic drinking of jurema was first described in 1788. [41] It was drunk in shamanic healing ceremonies within the Jurema Cult (O Culto da Jurema), which is thought to have emerged in the indigenous communities of the Tupí people.

After the Hispanics’ arrival and until the 19th century, drinking jurema was labeled as witchcraft by the colonizers, with many of the users being arrested or worse for these “demonic activities.” The cult either survived into the 20th century, in a much more underground fashion, or it reemerged then as a means of strengthening the frail cultural identity of the decimated indigenous populations. Today, not many jurema-drinking communities are known; one of them is Atica. [42]

As for Kaapi and the indigenous shamanistic practices, they underwent the same suppression with the arrival of the colonists. The brew survived, though, and its use was widely spread not only throughout Brazil, but throughout South America and the world, by the emergence of several syncretic religions which use hoasca (Kaapi) in their ceremonies. [43] We will talk about these movements in the following section.

Today, drinking Kaapi is illegal in Brazil in indigenous contexts; it’s only legal for church members in a religious setting.

Colombia

Thanks to extraordinary pioneering efforts of numerous ethnobotanists starting with Richard Spruce in the second half of the 19th century, abundant records of indigenous Colombian shamanism and mythology are available.

In 1852, Spruce first reported the use of B. caapi brews in the Tukano indigenous culture along the Vaupés River in the southeast part of Colombia (Spruce, 1873). After him came Theodor Koch-Grünberg, who also stayed with the Tukanos in the extreme northwest of Brazil, studying their belief system and customs around the use of the brew he called “cayapi.” [44]

He recounted that the brew can “induce delightful hallucinations, which have been compared to those due to hashish. All things appear to be huge and gorgeously colored, there are visions of motley-tinted snakes and of erotic experiences.”

He also described the ceremony atmosphere and the preparation of the brew:

“Some partakers fall into a deep sleep, awakening with severe headache. On novices the brew acts as an emetic [...] Women never drink cayapi, the preparation of which is wholly a masculine task. The men pound up the roots, stems, and leaves of the shrub into a greenish-brown mass, which is washed with water, squeezed dry, and again pounded and washed. The resulting substance, not unlike cow dung in appearance, is strained through a double sifter into the bellied cayapi urn, which is covered with leaves and placed outdoors. [...] Though never washed, the vessel is now and then repainted with the same yellow designs on a dark-red background.”

It wasn’t until the explorations of Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff that we got a deeper insight into the elaborate cosmology of this fascinating indigenous group. He portrayed in great detail what the Tukanos believed happens when drinking the brew—the passage from deyόri turi, the regular world, to deyόbiri turi, the “invisible” world. According to indigenous belief, this is “a process of birth; the rupture of the plane (or shell) is the rupture of the placenta, followed by the entrance into another dimension of existence and cognition”.

Reichel-Dolmatoff also described the complex symbology of the Tukanos, their understanding of astronomy, the shamanic training, initiation, and healing practices, their notion of sexuality, and numerous other aspects of everyday life in this culture. [45]

Colombian ayahuasca use later gained worldwide exposure through the journeys of William Burroughs, whose correspondence with Allen Ginsberg was chronicled in the highly-acclaimed beat generation work The Yagé Letters. [46]

The name of the brew in Colombia, yagé, stands for a masculine spirit, as opposed to traditions in which it is called ayahuasca. This makes up for one of the main differences in the shamanic tone associated with Colombian healing practices. Otherwise, and aside from individual cultural distinctions in each indigenous community (for example, the Tukanos are known to hold communal ayahuasca ceremonies with song and dance), the general aspects of shamanism are alike those in neighboring Andean countries.

Although Colombia suffered tremendous human and cultural losses in the decade of rubber tapping in the early 20th century, indigenous yagé traditions survived and retained much of their authenticity even despite the substantial development of ayahuasca tourism in this country. Indigenous yagé use is legal and abundant in Colombia.

Photo credit: Jethro Tanner - Aniwa Elders, Prayer From the Heart For Peace

Ecuador

Ecuador is home to an astounding number of indigenous groups. Most of them are distributed throughout the Amazonian region; some of the better known ones include the: Napo Runa, Pastaza Runa, Waoranis, Achuars, Shuars, Cofanes, Siona-Secoya, Shiwiars, Záparos, Tagaeris, and Taromenanes.

However, there are many indigenous cultures inhabiting the rest of the country, too. In the Andes there are the Otavalos, Salasacas, Cañaris, Saraguros and Awás, while the Pacific Coast is home to the Chachis, Huancavilcas and Tsáchilas. Some of these populations use ayahuasca and contribute to the conservation of Ecuadorian indigenous history and cultural legacy.

The Napo Runa belong to the Kichwas, the most populous ethnic group in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Their culture is thought to possess some of the most extensive knowledge on the application of healing plants in the Amazon. After the arrival of the colonists, with the spread of the diseases they brought, the Napo Runa are said to have quickly learned to harness the healing powers of up to 1200 different plant medicines. [47]

It’s likely that the synergy of B. caapi and D. cabrerana was discovered somewhere along the upper Putumayo River, on the border between Ecuador and Colombia; possibly around this time when the Napo Runa were expanding their knowledge of the healing flora around them. Prior to that, and well after in many communities and/or contexts, the brew would be made only from B. caapi.

Traditionally, indigenous ayahuasca practices in Ecuador come down to a few use case scenarios.

In most communities and cases, the shaman would drink alone for divination, diagnostic, and healing purposes. Most of the community, aside from the shaman’s family, would be hesitant to try the brew on account of its grueling effects. However, if the shaman deemed it necessary, a patient would need to drink.

In some indigenous groups, such as in the Waorani culture, the males in the community would fast on ayahuasca in order to sharpen their senses and reflexes and become better hunters and warriors. [48]

Barring the northeastern part of Ecuador, most of the country did not receive much exposure to the colonization, was far enough away to avoid tremendous losses during the rubber boom era, and it has not undergone massive commercialization as a consequence of ayahuasca tourism like its southern neighbor, Peru. Thanks to this, the indigenous shamanic lineage and traditions have mostly been conserved and Ecuador stands out in terms of availability of authentic ayahuasca experiences.

Today, indigenous ayahuasca use is legal and abundant in Ecuador, and it’s quite possible to find well-respected shamanic families of 3-4 generations living together on their heritage property, where an elder shaman with 50+ years of experience serves the medicine on a nightly basis.

Peru

Peru is the South American country most commonly associated with ayahuasca use, and for a good reason. The land is home to 51 different indigenous groups with a combined population of 6 million, significantly more than that of Ecuador and Colombia combined.

Most of them (over 80%) belong to the Quechua group, whose language the word ayahuasca comes from. They inhabit the highlands and coastal region of the country. In the Amazon, most well-known ayahuasca-using communities include the: Achuar, Asháninka, Harakmbut, Huambisa, Jivaro (Shuar), Shipibo, and Tukano peoples.

Iquitos, the largest city in the world which is not reachable by road, is also the main global ayahuasca hub. The brew is offered there on every corner, and the retreat center infrastructure is up to par with the influx of tourism, which has skyrocketed over the past few decades.

It’s assumed that the combination of B. caapi and P. viridis originated in the vicinity of present-day Iquitos, around the confluence of the Napo and the Amazon Rivers. It’s also possible that the tradition of holding ayahuasca ceremonies for a community of people in need of spiritual healing and growth emerged here; at least, the first record of this style of ayahuasca healing comes from the slums of Iquitos. [49]

The colonization in Peru was followed by mass intermarriages, creating a mestizo culture which melded not just the genes, but the cultures of the two worlds as well. The rubber boom, then, as described, saw a large-scale recruitment of these mestizo offspring in curanderismo, spawning generations of mestizo healers and a novel shamanic tradition which integrated Catholic symbols and elements into indigenous practices.

Fast forward another century to the ayahuasca tourism boom, which precipitated mass migrations of indigenous peoples from their small communities in the rainforest to more urban areas in search of better education and income. Many entered the ayahuasca service industry, either as (actual or charlatan) shamanic healers or by capitalizing on the gringo demand in other ways.

After five centuries of population change, belief system evolution, and tourism expansion, true indigenous tradition in Peru is not as present as it once was; even some indigenous practices took on elements of Catholicism. However, it still exists, and these healers can be found mostly in urban areas, mainly ayahuasca hotspots such as Iquitos, Tarapoto, Pucallpa, and Cusco. The true challenge in Peru is not finding indigenous practitioners, but ones with an authentic healing ethics rather than shortsighted financial motivations.

Learn about the Declaration Made by the Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon at the World Ayahuasca Conference 2019.

Syncretic Churches

Santo Daime

Santo Daime was formed by Raimundo Irineu Serra, later known as Mestre Irineu, a child of African-descent migrants who moved to the Western Amazon region in his youth, attracted to the booming rubber tapping industry. He experienced a series of visions while drinking ayahuasca in solitude, and eventually started conducting spiritual healing ceremonies using the brew.

Artist credit: Helena Arturaleza - Birds of Paradise

On May 26, 1930, Mestre Irineu led the first “work” (ceremony) of his newly formed church, which he named Centro de Iluminação Cristã Luz Universal, or CICLU. He discarded the hierarchical rankings of the Círculo de Regeneração e Fé (his previous church and the first ever syncretic ayahuasca religion), various elements of Catholicism, and the spirit possession practices of his own Afro-Brazilian heritage. Conversely, he adopted the notions of the Eternal Father, the Divine Mother, Jesus Christ the Redeemer, and a Doctrine which would be revealed to each person joining his church.

Santo Daime ceremonies involve many hours of activities, or “works”, including: silent, seated meditations; dances with simple geometrical choreographies and singing of hymns; masses for the dead; and the feitio, or ritualized group preparation of the sacramental brew, which Irineu renamed to Daime. The members would wear uniforms which communicated unity and equality.

In 1971, Mestre Irineu died and the Santo Daime movement split into two lineages: the traditionalists and the innovators. Eventually, the innovators, who integrated African-style practices of physical mediumship and veneration of the orixás (Yoruba deities) into the movement, went on to spread Santo Daime throughout Brazil and much of the world.

Today, aside from their home country, Santo Daime ayahuasca churches can be found in Europe, the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, and elsewhere. Although illegal in many parts of the world, Santo Daime churches have, after a number of legal disputes, received exemption for holding their ceremonies in the US, Canada, and the Netherlands.

Santo Daime

The Beneficent Spiritist Center União do Vegetal, or UDV for short, was formed on July 22, 1961, by Brazilian rubber tapper José Gabriel da Costa, known as Mestre Gabriel. The name of the church means “Union of the Plants,” referring to the hoasca tea (ayahuasca), whose brewing process reflects this union.

The UDV combines Christianity with the notions of reincarnation and the progress of the soul toward higher spiritual levels. This church has a hierarchical order, with the more advanced teachings being reserved for higher-level members. Their ceremonies involve consuming hoasca for concentration, then sitting in long periods of silent meditation and listening to teachings from church elders.

Today, the UDV ayahuasca church counts around 20,000 members throughout 200 branches in all Brazilian states, several branches in the US (Colorado, New Mexico, California, Connecticut, Texas, Florida, and Washington), and some in Peru, Australia, and several countries in Europe. The UDV leadership in Brazil holds strict hierarchical control over all UDV congregations and members, and new members are inducted with great scrutiny; this accounts for the slow growth of the movement.

The UDV set several legal precedents when importing their religion (or, more precisely, ayahuasca use) into the US. After years of battling the country in court, they were granted exemption based on religious freedom, ultimately paving the way for the Santo Daime church as well as the legal use of other psychedelics in a religious context.

Barquinha

The church of Barquinha (The Little Boat) was founded by Daniel Pereira de Mattos, known as Frei Daniel, in the state of Acre in Brazil in 1945 or 1947.

Frei Daniel had a vision in which two angels gave him instructions to start a Christian doctrine in which suffering souls would be helped by trained church members, who would have the healer spirits incorporated in them “irradiate” those in need of help. The movement was to be based entirely on charity and the healing was to be offered to the general public completely free of charge. Other forms of charity would also be performed by the church members, and they include acts like adopting children, organizing events for poor children, and hosting visitors in their homes.

The healing services were offered within a worship ceremony which involves devotional singing and praying following the sacramental drinking of Daime or hoasca. The Barquinha is the only one of the three syncretic religions in which there are no assumptions of supernatural aspects in its founder. It is also the only one in which hoasca is not drunk in all rituals nor is it obligatory for all attendees, who need not be members to participate in the ceremonies.

Frei Daniel had been a follower of Mestre Irineu, the founder of the Santo Daime church. He reported his vision to Irineu, who would not accept the concept of incorporation for his movement but amicably authorized Frei Daniel to form his own church. The Barquinha has made no effort to spread and remains confined to the state of Acre.

New Age Circles

As ayahuasca gains worldwide popularity and gets served by non-native ayahuasqueros in vastly different contexts to those it originates from, so do are the traditions adapted to suit the individual styles of expression of ceremony facilitators.

Many people came to the Amazon and discovered ayahuasca after a lifetime of following teachings from various metaphysical lineages. Unlike native shamans, whose training comes from a belief system that doesn’t have that much variance throughout the Amazon basin, and who aren’t typically exposed to different ideologies about life and the universe, gringo shamans tend to innovate on what they had experienced in the rainforest and fuse it with their own understanding of truth.

As can be seen in the development of syncretic religions in Brazil and mestizo shamanism itself, ayahuasca ceremonies evolve throughout time. These changes may be regarded as inauthentic by some, but they, just like the evolution of language when there’s a merging of culture, are a natural progression of life and an authentic expression of the souls of those who preach and those who follow.

Artist credit: Carlos Cabán - Our Mothers

Mostly, in New Age ayahuasca circles, various mindfulness techniques, elements from different belief systems, and divergent artistic tendencies are integrated into the ceremony. These can be anything from yoga and breathwork to bodywork and dance, to musical accompaniment which may or may not be inspired by indigenous icaros.

Music likely makes up the biggest departure from native South American ayahuasca ceremonies. Many gringo shamans do not sing icaros, but instead play folk or indigenous tunes on an instrument (typically guitar) or play a prepared playlist. As we noted, icaros are shaman’s fundamental tools; they are used for setting up and protecting a safe spiritual space, diagnosing and healing illness, vanquishing malevolent entities, and creating and guiding drinkers through spiritual realms. It’s a question whether ceremony facilitation without icaros can really be called shamanism.

An even bigger question is where these different modalities of healing work are channeled from. Icaros, for example, are “given” to the shamans by their plant spirit allies once their connection is strong enough; if one sings a song which was not “gifted” to them from the astral plains but is merely an interpretation of a local tune they heard in Peru, they aren’t so much guiding the experience as much as they are padding it with a backing track. For the ceremony participants, however, who are most often ayahuasca-naïve, this represents the full extent of ayahuasca healing they can experience.

Clearly, there is plenty of room for manipulation and pretension in these circles. That said, there are also some extremely unique and authentic novel directions the ayahuasca ceremony is being taken in by individuals who have already established themselves as strong energetic presences and purveyors of wisdom and healing coming from sources and traditions quite disparate from those of the Amazon.

The New Age of ayahuasca healing is in its infancy; it remains to be seen how the landscape will be moulded by those who take on the responsibility to wield this sacred medicine in different cultural contexts. Until then, and as always, tune in to what feels right and reject that which doesn’t. In the following sections we will talk about how best to go about assessing the safety, reliability, and authenticity of an ayahuasca ceremony, retreat, and facilitator.

You may be curious about the Coronavirus Risks Associated with Joining Ayahuasca Ceremonies at this time.

Part 5:

Practical

Now that you know a little about the risks and benefits of ayahuasca, how do you go about finding an ayahuasca ceremony?

Here are some tips to help you understand the different kinds of ayahuasca experiences you can have, and how to go about researching the ideal ayahuasca shaman, facilitator, or retreat for you.

Once you've found an ayahuasca provider that feels safe, qualified and good, the next step is preparation for this powerful, transformative experience.

When your ceremony is over, the real transformational work begins with the integration process, so that you can heal, reclaim your wholeness, and create lasting, positive change in your life.

Research & Considerations

There are many things to consider when choosing an ayahuasca retreat. Aside from looking out for the style of ceremony and specific retreat conditions you prefer, keep in mind that you will also be placing your well-being and even life in the hands of your shaman or facilitator.

The Retreat Center

Here are some basic things to consider when searching for an ideal ayahuasca retreat center:

- Location. Is the retreat easy to get to? Is it in the jungle or in more urban or rural spot? Do you need to take an additional charter flight or a boat to get there?

- Legality. Is ayahuasca legal in the country where the retreat is being held? Many countries consider DMT to be a prohibited substance, and some have laws specific to ayahuasca. We encourage you to learn about the local regulations and respect the law.

- Religion. Some retreats or groups, like Santo Daime or most mestizo shamanic practices, have religious roots or elements in the ceremony, which may not be ideal for everyone. Consider whether a secular retreat would be better for you.

- The practitioner. You may feel more comfortable with an indigenous practitioner rather than a Western one – check out who is running the ceremony at your retreat (more on this below).

- Ceremony style. Some retreats require the group to move or chant together, or even undertake group tasks during the experience. If you’d rather trip without group interactions, make sure to inquire about the ceremony style at the retreat center.

- Amenities. Are there lodgings at the retreat? Do they provide food? How comfortable does the ceremony space look? Are there luxuries such as workshops or massages on offer? Consider what level of comfort you will require to make your experience comfortable enough.

- Cost. This will very much be linked to the level of luxury of the retreat. Consider what is within your means, but remember that expert facilitators and convenience are not cheap!

- Requirements and restrictions. Some retreats will require you to follow a diet or practice meditation before the ceremony. If this isn’t for you, check to make sure what the retreat policy is beforehand. Some retreats require you to pass a medical screening to check for a family history of mental health problems, or heart conditions.

- Purpose. Why are you attending a retreat? If it’s for therapeutic purposes for a serious condition, consider the safety of the retreat. Are there trained therapists on hand? Is there a medic at the retreat? Will this retreat center offer you the best chance of finding what you’re looking for?

The Shaman / Facilitator

Once you have settled on the retreat that looks right for you, it’s important to consider the shaman who will be running the ceremony.

The effects of ayahuasca are very powerful and can leave you in a vulnerable state. Because of this, you must have complete trust in the group of people running the retreat and the shaman who will be holding the space and guiding the journey.

Unfortunately, the booming ayahuasca market has spawned a number of charlatans, frauds, and sexual predators. The vast majority of ayahuasqueros are still good, honest, well-trained, and authentic – but it won’t hurt to protect yourself from the fakes.

Consider finding out the answers to these questions about your shaman, and if possible ask the shaman or organizer themselves:

Artist credit: Tessa Mythos - Ayotl - Water Heart of the Jungle

- Are they trained? Are they a genuine healer, or do they just pour the medicine and stand around in case they’re needed? How long did they train for, and with whom? The answers to these questions will help you establish whether your shaman is genuinely knowledgeable. Most traditional shamans will have undergone years of training that includes a strict diet, sexual abstinence, and a lot of ayahuasca. Ideally, you should sit with a shaman who has been working with the medicine for over a decade.

- What tradition do they follow? What is their lineage? Where are they from? These questions will help you understand the shaman’s background and unique perspective on the medicine. For help deciding whether an indigenous shaman or Western facilitator is best for you, check out our article Indigenous or Western Ayahuasca Shamans – Which is Best?

- What other healing techniques do they use? Some shamans will use plants like tobacco or kambo in their ceremonies. Make sure you know this ahead of time so you can opt out if you don’t feel comfortable with it.

- What’s in the brew? Does the shaman make it themselves? If they don’t, where does it come from and what’s in it? It’s important to know what you’re being handed on the day of the ceremony, and that it’s a recipe the shaman is very familiar with.

- Do they have restrictions? Some shamans will not work with you if you are looking to treat certain conditions. Make sure the shaman is trained to provide whatever support you may require.

- What extra support will be available? There should be someone available during the ceremony to answer questions, or provide assistance, who is not the shaman themselves. Make sure someone is accountable for the shaman.

- What’s the dosage? Does the shaman offer a range of different doses depending on your comfort level? Will there be an opportunity to take a second dose if your first was too weak?