Ayahuasca Ceremonies Huni Kuin Style, at the Eskawata Kayawe Festival

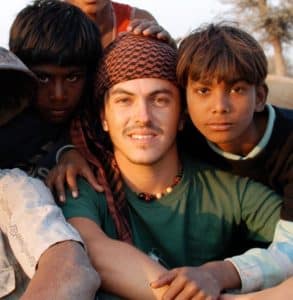

This guest article by Iván Sawyer García takes us into the Brazilian Amazon, and gives us a glimpse of the Huni Kuin way of life. Photographs by the author.

It is night and I am lying in my hammock. I am in Novo Futuro village, located in a remote region of the state of Acre in Brazil. The air is humid, and as the twilight arrives the sound of the jungle is amplified. I can clearly hear how the jungle night crowds around my cabin. Countless sounds of insects, frogs and birds make up a natural orchestra. I am so overwhelmed with the different emotions that come from being in this place, that I hardly even notice the hundreds of mosquitoes that surround my hammock and try to find a hole in the mosquito net to enter and peck at their whim.

It has been three days of pilgrimage, traveling with a group of people to attend the Eskawata Kayawe festival, meaning “transforming energy of the jungle.” The festival was organized by Ninawa Pai da Mata and Vinicius Romão, a young Brazilian from São Paulo who is already part of this tribe. Txai Vinicius (the term “Txai” means “friend” or “brother from another mother” in Hatxa Kuin, the language of the Huni Kuin), is dedicated to bringing groups of travelers interested in knowing the forest and culture of this extraordinary site and who also seek to participate in the healing rituals that are promoted with the medicine of ayahuasca or nixi pãe.

Journey to the Heart of the Amazon

We travel for three days by boat, leaving the nearest port of the small town of Tarauacá, State of Acre, Brazil. The journey was not easy. We set sail just after dawn and only took a few breaks along the way, taking advantage of the sandbars of the river to cool off and stretch our legs.

The boat was driven by two different boat drivers and their families, who with resounding kindness and wide smiles prepared for us breakfast, lunch and dinner in a kitchen that they improvised themselves. It was not a trip full of amenities, but the love, kindness and food that the crew gave us were exceptional.

Despite the apparent discomfort, I will never regret the decision to go on an adventure and learn how to live and travel in the depths of the Amazon rainforest – a place full of mysteries, dangers, exuberant life; but also deep death.

During the crossing I was accompanied by a Spaniard from Madrid, an American based in Rio de Janeiro, a 23 year old Japanese painter, and Francisco; a Brazilian anthropologist who was travelling to this region for the third time. Francisco explained to me how fortunate we were to be able to reach this place in the Amazon, as there are few who are allowed to access this remote area.

At dusk, the motorists docked the ship to spend the night. Inside the ship we hung our hammocks and in a few minutes we fell asleep, lulled by the sound of the jungle. We were tired and we had to leave very early to make the most of the sunny hours.

Three days later, we finally arrived at our destination, the small village of Novo Futuro, a relatively new settlement and the last of the six Huni Kuin villages that are located on the Humaitá River. Past this village the territory becomes inhospitable and dangerous. In it live the indios bravos (the “brave tribes”), or uncontacted peoples that the rest of the inhabitants of the Amazon fear, given their reputation for being aggressive. I try to imagine what the Huni Kuin were like before their contact with the Western man.

Upon arriving at the village, I felt like I was in a dream. On the bank of the river we were greeted by a group of women and children singing in their language with their faces painted intricate designs. I must say that it was a tremendous honor for me to be received in this way and it was a great relief to finally set foot on the mainland. At the bottom of this endearing scene I saw the village, a small town by the river, whose cabins were built with sticks and palm roofs.

Some young people showed us where we were staying and helped us with our bags. We were accommodated in simple cabins where we hung our hammocks. My cabin was the last one, all the way at the back of the village, behind me was the immensity of the jungle completely surrounding me.

After settling, they called us into a huge structure made of palm leaves called a shubuã (maloca in other parts of the Amazon), the sacred house of the Huni Kuin, where they perform their weekly ceremonies of nixi pãe or ayahuasca. As soon as we arrived, the villagers invited us to join a session of traditional dances and songs or Katxanawa, for which all the members of the village paint their faces with intricate designs, they are adorned with necklaces of seeds and colored chaquiras and they crown with beautiful plumes of feathers. Dancing and singing also welcomed us; They made us part of their clan. Now we were family.

A group of visitors approached Vinicius to follow him through a muddy path that crosses the village. We passed through the kitchen, a palm structure located on an elevated platform that prevents the passage of the animals of the jungle. Huge bouquets of bananas hung on the sides, smoke rising above the communal kitchen. It is in this wonderful space where women make food: Rice, fish, bananas and cassava prepared in multiple ways in large pots.

Opening the Community to Outsiders

While we were walking, Vinicius explained that until recently it was rare for foreign visitors to arrive. It was not easy for the community to open up to the possibility of receiving foreigners. Their experiences with missionaries and employers who had not allowed them to exercise their culture, language and spiritual practices had left them with a very negative impression of the outside world, and for many years they refused to receive visitors for fear that history would repeat itself.

Today there are no more missionaries or rubber tappers on their land and the people Huni Kuin live in peace; They can exercise their culture and speak their language in complete freedom. Vinicius’ own perception is that today they enjoy greater rights over their territory, so they themselves consider living in the “Righteous Times” or Xina Bena.

Unfortunately, the coming to power of Bolsonaro is putting this freedom and even the survival of the Huni Kuin in serious danger.

Find out here What’s a “Traditional” Ayahuasca Ceremony?

Kene – the Sacred Geometry of Huni Kuin Art

It is noteworthy that during their ceremonies and festivals, both men and women paint their faces and bodies with very particular designs. Carolina, a Brazilian from Rio de Janeiro who helps as a coordinator in the kitchen and who had her whole face painted, explained that this painting is known as kene kuin – the true design – and that this is an important emblem of the people Huni Kuin.

For them, these designs are a very important element that contributes to enhancing the beauty of people and things. In order to paint the bold, geometric shapes found in their pottery, textiles and beadwork onto their bodies and faces, the Huni Kuin use a fruit called Nané (also known as jenipapo), which is the fruit of the jenipapeiro tree (Genipa americana) of the Rubiaceae family.

The black juice of the jenipapo fruit is used for body and face painting. When the juice is left to dry on the skin after painting, it darkens into a semi-permanent dye, that eventually fades with every wash. When the fruit juice is mixed with ash, it makes a darker dye that is no longer semi-permanent. Strong, black lines can be painted all over the face and body in bold geometric patterns, then washed off immediately.

The Huni Kuin paint their face and body during festivals, ceremonies, and in the celebration of their rites of passage. Young children are generally not painted with designs, but sometimes they are dyed from head to toe with jenipapo. Carolina told me that when one of the men in the house goes out to collect jenipapo in the jungle, when he returns, it is almost certain that someone is waiting to mix the paint and invite others to paint. The same basic motifs or designs used on the face are used in the body, in ceramics and in cotton fabrics, in baskets and even in the decorative objects of the kitchen.

The painting is associated with a new phase in the life of a person, an important transition during which it is desirable to accentuate the beauty of the body. In this sense, the painting indicates that it is going through a very important vital event. Designs fade as the days go by and are only reapplied on other special occasions.

Becoming One of the True People

You can tell Txai Vinicius is an enthuthiast of indigenous cultures and shamanism. He is originally from São Paulo, but since 2013 he lives in the city of Tarauacá, and works on different projects to bring improvements to the villages through the association Povos de Terra-Apoti.

I asked him about the culture and history of this town that today is known worldwide for its ceremonial use of the nixi pãe or ayahuasca, for its shamanic songs and also for the snuff, a type of mixture of tobacco with herbs that is ingested through the nasal passage.

Then I had time to investigate further and I discovered that their language comes from a group of languages called Pano to which several groups belong, including Yawanawa, Shawadawã and Jaminawá.

Txai Vinicius told us that upon his arrival in the 1970s, the first thing anthropologists saw the Huni Kuin do was to fiddle with the bats. One of them asked them what they were doing, to which they replied that they played with the kaxi nawa (bats). After this anecdote, anthropologists named the people as the Kaxinawá or bat people. However, they always considered themselves Huni Kuin or real people. Another anecdote suggests that the name Kaxinawá was actually an expletive with which other neighboring tribes insulted the Huni Kuin.

During one of the many meals in the village I met Francisco, the anthropologist of Sao Paulo. He explained to me that this town has been almost half a century after being contacted, it was the rubber tappers who first entered this land in search of rubber, which was once a highly appreciated material since it was used in the manufacture of tires and other waterproof and insulating materials.

Meeting the Sacred Jiboia

At night we are all called to the shubuã for ceremony. It is a gigantic structure in a rectangular shape with tall wooden poles along the center. The ceremony begins with a prayer and blessing followed by the serving of nixi pãe, as they call ayahuasca, the sacred brew. The first part of the ceremony is led by the Txanas or singers that recite traditional chants to invoke the forest spirits, or that is what it seems like to me. These chants resemble Tibetan chants somehow with a mantric, repetitive melody and in a low-tone voice.

I start feeling sick and I get up, a density within me seeks to be released. I rush outside and can’t help but puke in a bush nearby. I can hardly stay on my feet. Immediately after I am filled with a sense of relief. I feel I have released a strong density from my body, something that was causing a lot of stagnant energy. I am not sure if it was something physical or spiritual but anyhow it’s gone now.

I am filled with gratitude to these people and this medicine. I walk towards an outside fireplace kept by a few Huni Kuin men that silently watch over the sacred fire a few feet outside the door of the ceremonial building. I sit in reverence towards the powerful immensity, grateful for being alive, grateful for being here, grateful for these people and this medicine. Finally, I feel the need to go back into the ceremonial building just as the chief, Ninawa, announces the beginning of the live music part of the night.

As soon as the music begins the Huni Kuin form a line of people that dance around the building in the shape of a snake or “jiboia” (anaconda); this is known as the jiboia dance. Everyone follows along with their voice, the music fills every part of my body and soul that lifts me up into a heavenly realm. We dance and sing until dawn and I feel as the jiboia dances through us. She is a massive rainbow serpent filled with healing energy and love. She has loved and protected the jungle people for millennia. She welcomes us here. She is the jiboia.

Blessings from the Sacred Tree

After several days of being in the village, I decided to venture towards the Samauma, a very special tree that is located in the jungle, about a kilometer from the village. This tree is very sacred to the Huni Kuin because inhabits it Yuxibú, the creator. Upon arrival at the tree I was received by the grandmother, who arrived from another region where the Huni Kuin people also live. The grandmother asked me to please bow down before the Samauma to ask permission to be here and told me that if I concentrated and had a clean mind and heart, he would listen to my dreams and bless my destiny.

The next day they took us back to Samauma. Once there, they offered us a baptism with a type of pepper or rampayã, after which, they assured us, our voice would improve markedly and we could sing better and have a good memory. For the Huni Kuin singing is very important, they consider it a tool of connection with the spirit. The medicine is a very spicy substance that when ingested causes a great burning in the mouth. I wonder if this will help me to learn some of their songs.

In the afternoon, our little house was visited by different members of the village, many of them were eager to meet us; others simply wanted to exchange some object. Some women sold us handicrafts, a boy came to teach us to sing and at the end of the evening, he managed to exchange a snuff applicator made of crocodile bone for a portable lamp.

My time in the village came to an end. I’m moved by this encounter and also very worried because the boat back, Francisco told me that the way of life of the people Huni Kuin is being threatened by the current Bolsonaro government, which with its territorial policies promotes the mining, agricultural and livestock exploitation of the Brazilian Amazon.

When I leave the village my eyes fill with tears of emotion. I feel that I met my true tribe. I will be back someday!

About the Author

Ivan Sawyer García is a cultural entrepreneur, media producer and indigenous rights activist. Among other things he has been involved in different of cultural exchange, sustainability and preservation of indigenous knowledge in different parts of North and South America for more than a decade. He has collaborated with different organizations such as Unify.org, NuMundo.org, Guardians of the Forest and with events such as the First World Forum on the Rights of Nature, Global Eclipse Festival, among others.

Ivan is the founder of Voces de Amerikua, a collaborative media laboratory that supports and promotes the voices of indigenous peoples of North, Central and South America and their efforts to protect their Culture, Land and Rights, using impact campaigns, social media and documentaries. Voces de Amerikua works with musicians, creators and with the communities themselves to share the reality of the environmental and human rights problems that the different communities face in this region of the planet today.