Richard Evans Schultes: The Father of Modern Ethnobotany

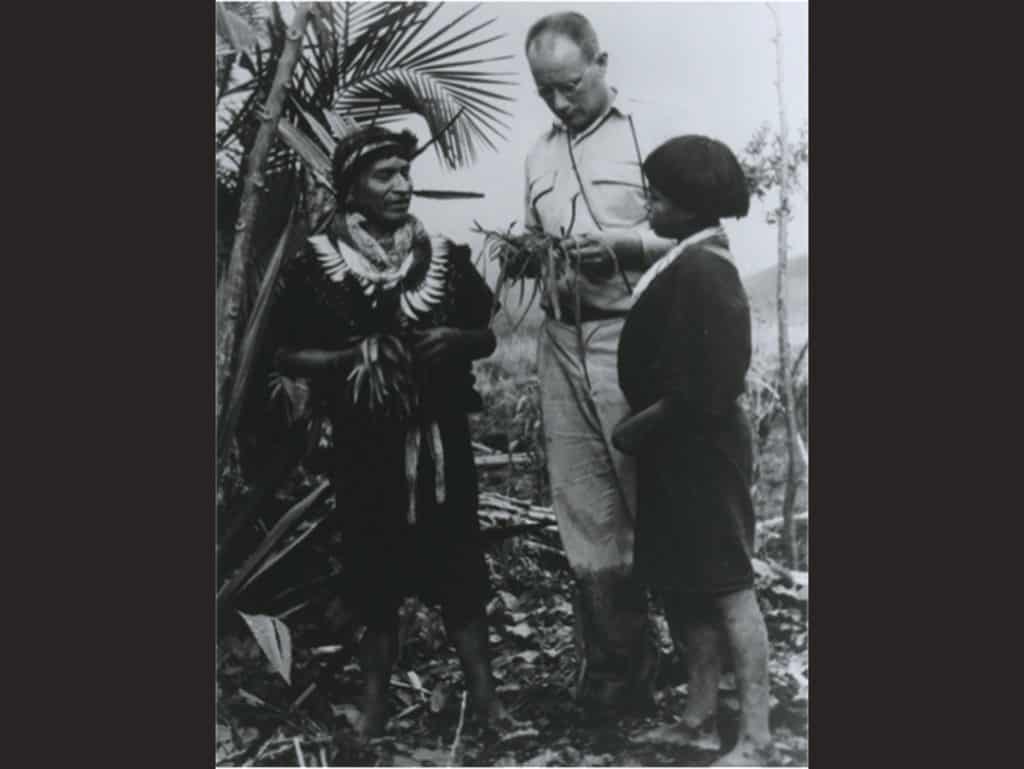

Image: Richard Evans Schultes with Amazonian shaman Salvador Chindoy (via Wikicommons)

Richard Evans Schultes was undoubtedly one of the most important plant explorers of the 20th century. In recounting Schultes’ life, research, and adventures, images of the archetypal explorer come to mind – he emerges out of the dense jungle foliage with his machete, or floating downstream one of the tributaries of the Apaporis River on his tin canoe in search of the sacred fount of knowledge as an almost fictional character. Moving beyond the incredulous fantasy of Indiana Jones, cast aside your doubt and keep reading, because the epic story we are about to tell is one that Schultes really lived.

Schultes is renowned for the extensive field research that he undertook in the Americas, particularly in the northwest Amazon. In December 1941, Schultes began his near 10-year exploration of the Amazon rainforest, investigating how indigenous peoples used plants in medicinal, ritual, and daily contexts. In a decade of interminable fieldwork, he identified more than 24,000 species of plants of which 300 were previously undiscovered by science.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts in January 1915, Dr. Schultes is often referred to as the ‘father of contemporary ethnobotany.’ Ethnobotany comprises the study of how people across societies use plants in their daily lives. Schultes gave his definition of the term in an interview:

“Ethnobotany simply means someone who’s investigating plants used by [indigenous] societies in various parts of the world. It’s as simple as that. Ethnobotany has been around many, many, many thousands of years, and we are now trying to salvage some of the knowledge that [indigenous] societies have amassed over thousands of years and passed down from father to son orally. With every road that goes in, every airport, every missionary, every commercial person, even tourism, this is fast disappearing.”

The Medicine Trail

Around the age of five, Schultes became seriously ill with a stomach ailment, leading him to be bedridden for weeks. With the idea of keeping his child’s mind active, his father took out a book from the public library, Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and the Andes by the 19th century English botanist Richard E. Spruce, for his son to read. The vivid images of the book imprinted on the mind of the young boy and no doubt played a role in his fascination with plants later in life.

Originally a medical student at Harvard, Schultes changed his degree entirely after deciding to enroll in an undergraduate course entitled “Plants and Human Affairs,” taught by the distinguished orchidologist and Director of the Harvard Botanical Museum, Oakes Ames.

During this course, he had to write a term paper, and wanting to get it out of the way quickly, he selected the slimmest volume on the bookshelf: Mescal: The Divine Plant and Its Psychological Effects, an obscure book written in 1928 by the German psychiatrist Heinrich Klüver.

Being one of the earliest texts on the sacred peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii), Schultes found himself fascinated by what he had read, asking Ames if he could write his thesis on peyote. Ames agreed on the premise that Schultes would conduct his field research and gain firsthand knowledge of peyote amongst the Kiowa peoples of Oklahoma.

Schultes later went on to investigate teonanácatl (“Flesh of the Gods” in Nahuatl, the Aztec language) the ancient sacrament consumed by the Aztecs for divinatory purposes. It was previously believed that teonanácatl referred to peyote. However, Schultes believed it to be a mushroom, later identifying it as a magic mushroom (Psilocybe cubensis) consumed by the Mazatec peoples of Oaxaca, Mexico. He sent a sample to his friend and colleague, Albert Hofmann – the chemist who first synthesized LSD – who extracted to psychoactive compound psilocybin which is widely used in psychedelic psychotherapy and consciousness research today.

Later, Schultes made his way south to the Colombian Amazon with the primary purpose of researching arrow poisons (curare) which were subsequently used in Western medicine as muscle relaxants. This voyage made Schultes one of the first Westerners to live with the isolated tribes of the region, exploring vast territories of uncharted jungle which have not been revisited since. The records and photographs that he compiled throughout his explorations are among the only living documentation on indigenous cultures in expanses of the Amazon that now face unprecedented threats to their ways of life.

Additionally, Schultes became the first explorer to scientifically and taxonomically document the preparation and use of the visionary brew ayahuasca (from the Quechuan ayawaska meaning “vine of the soul”), pinpointing the chief ingredient as the Banisteriopsis caapi vine. He documented several varieties of ayahuasca, each prepared in a distinct manner by the various indigenous groups that he encountered, categorizing plants specific to varying admixtures such as the DMT-containing shrub Psychotria viridis (also called chacruna).

Visionary Plants & 1960s Psychedelia

With Schultes’ main purpose being to study sacred plants and explore new possible medicines, he unwittingly lay the foundations for the psychedelic era of the 1960s. His revolutionary research into the potent psychoactive plants of the Americas (peyote, magic mushrooms, ayahuasca, and Datura) came to influence central counterculture figures such as William Burroughs, Aldous Huxley, Terrence McKenna, and Carlos Castañeda, who conceived as hallucinogens as doors to self-knowledge.

With Schultes’ main purpose being to study sacred plants and explore new possible medicines, he unwittingly lay the foundations for the psychedelic era of the 1960s. His revolutionary research into the potent psychoactive plants of the Americas (peyote, magic mushrooms, ayahuasca, and Datura) came to influence central counterculture figures such as William Burroughs, Aldous Huxley, Terrence McKenna, and Carlos Castañeda, who conceived as hallucinogens as doors to self-knowledge.

Schultes’ obscure research into plant hallucinogens crystalized his books as cult classics amongst psychedelic users. In the 1970s, he co-authored Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers with Albert Hofmann, detailing the ritual uses and biochemical properties of our planet’s psychoactive plants throughout history. The book includes anthropological, chemical, botanical, historical, and geographic profiles of 91 psychoactive plants. A second book is Hallucinogenic Plants, featured in the series of US Golden Guide books on natural and man-made phenomena. Despite his unintentional influence on the hedonist drug takers of the 1960s, Schultes never failed to emphasize that “the sacred plants of Indians that should be studied for their medicinal value.”

According to Mark Plotkin and Brian Hettler, “The special significance of Schultes’ research derives in part from ideal timing: he arrived in the Amazon at a time of massive change for the peoples he encountered and ultimately for the great forest itself.”

Preserving Indigenous Wisdom & Protecting Our Rainforests

A relentless series of catastrophes are laying waste to indigenous culture – the challenges have come in the waves of colonialism, missionaries, rubber cutting, illegal logging, and deforestation for cattle ranching and oil drilling. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) stated that the Amazon rainforest “lost at least 17% of its forest cover in the last half-century due to human activity – mainly clearing trees to create new or larger farms and ranches.”

The ways of life of these indigenous groups are on the verge of being lost, alongside many plants, species, and trees, having devastating implications for our planet as a whole. In the words of Schultes: “Time is running out. The Indians’ botanical knowledge is disappearing even faster than the plants themselves.”

Schultes’ unparalleled research into indigenous cultures, visionary plants, and ritual provides a wealth of knowledge about a way of life that is quickly vanishing. His life legacy urges us to take collective action to preserve the biodiversity, indigenous knowledge and cultural wealth native to the Amazon.

Learn More:

An interactive map detailing Schultes’ journey is available through the Amazon Conservation Team, enabling you to retrace his illuminating adventures through photos, journal excerpts, botanical cuttings, and much more.

An interactive map detailing Schultes’ journey is available through the Amazon Conservation Team, enabling you to retrace his illuminating adventures through photos, journal excerpts, botanical cuttings, and much more.

A more in-depth account of Schultes’ travels can be read in Wade Davis’ One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rainforest. Davis was one of Schultes’ prized students, succeeding him with his own Amazonian expedition, setting out to study to indigenous use and botanical properties of the Coca leaf.

By Schultes himself, Vine of the Soul is a photographic essay supplemented by detailed descriptions of the indigenous use of the visionary brew ayahuasca. The vivid documentary photos transport you into a world where the use of healing plants, ritual and magic play an essential role in everyday existence.

Outstanding article with some very interesting links !

Many thanks !

James R. Pannozzi

Herbal Research

Why call indigenous people “primitive societies” in this article?

Hi KS, thanks for the feedback. This term is used in a quote from Schultes himself, and clearly his vernacular was dated. We have editorialized now to remove the phrase.